At the Margins of Alice Thornton's Books

"The great blank space provided by the margins" was filled with many kinds of text and image in early modern manuscripts and printed books, and a number of recent and current digital projects reflect the rise of scholarly interest in this material.[1] Of particular interest to the Alice Thornton's Books Project is the Marginalia and the Early Modern Woman Writer project which is investigating "how early modern women readers engaged with the margins of their books".[2]

However, these projects are largely interested in marginal annotations as readers' engagements with other people's writing. Thornton's marginalia, in the main, are author's signposts to the reader, like the use of the margins in early modern printed books to provide commentary, explanation, summaries or references, much of which would later make its way to the foot of the page.[3]

TEI and marginalia

Marginalia make a good example of the TEI's meaning-first emphasis. TEI has nothing like a <margin> tag or any tag that is exclusively for marginal use. As Paul Schaffner puts it, this is because

marginalia (even print marginalia, much more manuscript marginalia) can express many different relationships with the main text - substitution, addition, commentary, summary, expansion, bibliographic reference, labelling, heading, gloss, etc. - each of which might be captured with a different tag.[4]

Instead, markup depends on the nature of the marginal material, with extra attributes used for location (@place) and the identity of the author (@resp), if needed. Just some of the tags commonly used include <fw>, <label>, <note> and <add>.

However, this pragmatic flexibility brings its own problems, as noted by Laura Estill: it's difficult even within one project to search for all its marginal elements if they are marked up differently, and even more so to compare marginalia from different projects for any kind of quantitative text analysis.[5] One significant marginalia project eschewed TEI because of its downsides and limitations.[6] We won't go that far, but it is particularly important that the project's decisions are thought through and well documented.

Marginal signs

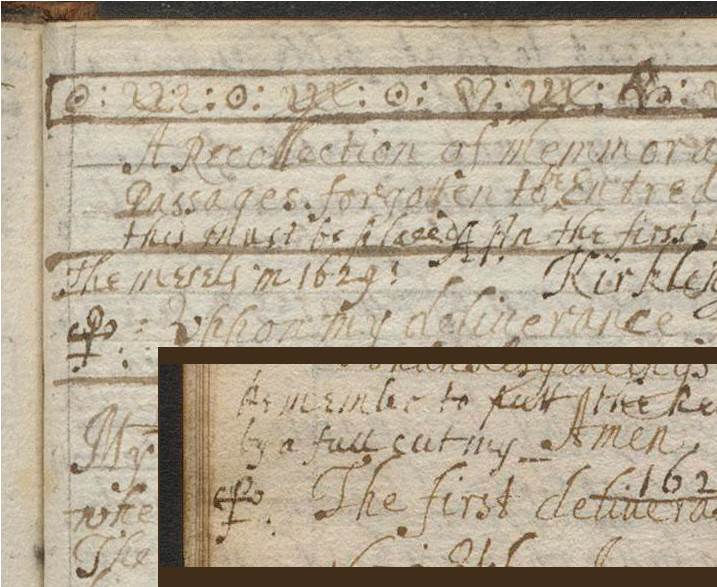

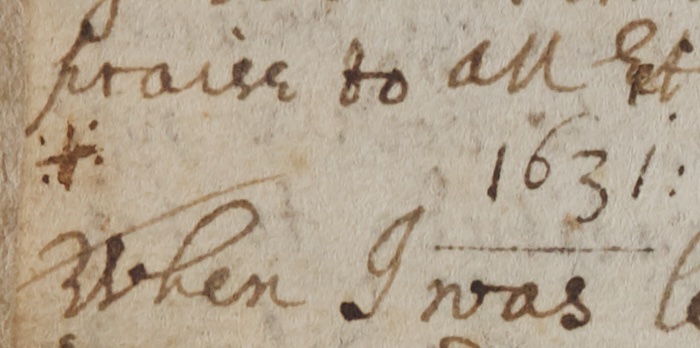

The books contain a wealth of intriguing graphical symbols; Thornton's frequently-used hearts have been discussed on this blog. A rarer set of symbols can be found in both Book 1 and Book of Remembrances. Both books include additional material at the end which Thornton had "forgotten" to enter in the main narrative, beginning in each case with an account of her falling and cutting her head at the age of three.[7] In Book 1, Thornton signals where she intends this story to be inserted in the main text (at p.8) by using a pair of decorative dagger (or obelus) symbols in the margin. I've called them "signes-de-renvoi" or "omission signs"; that may not be strictly accurate because the text being connected is not itself in the margin, but they are certainly being used as "bi-directional linking devices, requiring the reader to leave and return to the main text".[8] In Book of Remembrances, she uses instead a dotted cross, an early form of the asterisk. This time she places it only on the page she points to, not on both pages (see p.12 of the edition preview). Physically it isn't actually in the margin, but - like much of this tiny book - there isn't really space for a margin and it has been placed close to the edge of the page.[9]

Textual directions

There are plenty of marginal summaries of the main text in the the books, but they're far from evenly distributed: they appear only in Book 1 and Book 3. The material is most extensive in the first 64 pages of Book 3, which has a large space set aside throughout, but even there the marginal annotation stops very abruptly.[10]

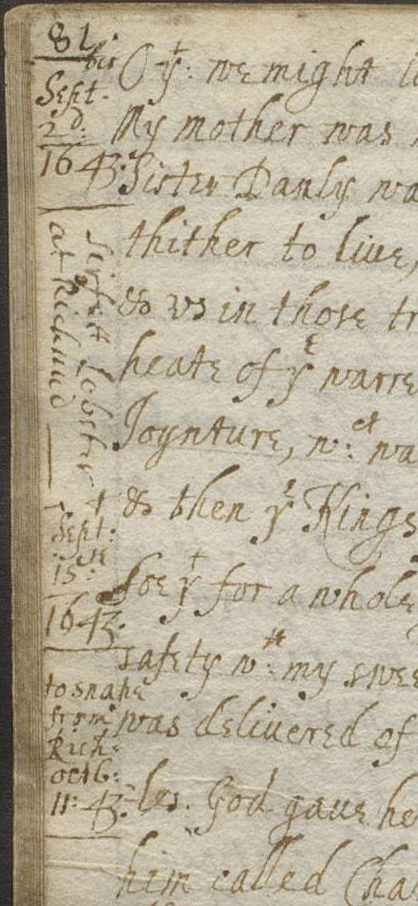

In Book 1, much of it is on one heavily annotated page (p.80), where she refers to five distinct events in the text. Oddly, however, not all of them relate to text on that page. So why are they there? Between pages 78 and 85, Thornton gives an account of her family's Civil War journey, leaving Chester in late August 1643 and eventually settling at Hipswell Hall in November 1644. But between those two moments, the narrative becomes rather disordered, jumping from events around Marston Moor and its aftermath in 1644, back to an episode of food poisoning in September 1643, and then forward again to arrival at Hipswell. The marginal notes on p.80 summarise the actual chronological order of events between September and November 1643, restoring the displaced "surfeit of lobster" to its proper place. So perhaps this was an attempt to provide a guide to the poor confused reader.

Thornton as scribe

In seventeenth-century England manuscript and print publication co-existed.[11] The marginal symbols in Alice Thornton's Books connect her in particular to the world of scribal publication; she seems to have understood scribal practices, even if she applied them in idiosyncratic and inconsistent ways (she was, after all, not a professional scribe and she didn't have an editor). Moreover, these marginal features, along with her other aids to the reader that are equally part of the apparatus of printed books, indicate that she was consciously writing for an audience, not simply for private consumption. Her uses of chapters and titles, page numbering and headings, indexes (really more like tables of contents), and other features, could all be similarly eccentric, but they are a key element of what makes Alice Thornton's Books books.

Erik Kwakkel, Books Before Print (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), 56, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781942401636. ↩︎

Several projects have focused on the marginalia of particular authors as readers, eg Whitman; Melville; Blake. ↩︎

Kwakkel, Books Before Print, chap. 4; Anthony Grafton, The Footnote: A Curious History (Harvard University Press, 1999). ↩︎

Paul Schaffner, 'Re: Marginalia', TEI-L Archives, 28 January 2014, https://listserv.brown.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind1401&L=TEI-L&D=0&P=68937. ↩︎

Laura Estill, 'Encoding the Edge: Manuscript Marginalia and the TEI', Digital Literary Studies 1, no. 1 (5 May 2016), https://journals.psu.edu/dls/article/view/59715 . ↩︎

Christopher Ohge, Publishing Scholarly Editions: Archives, Computing, and Experience (Cambridge University Press, 2021), 65-66, http://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/publishing-scholarly-editions/D5A9FCEA4DECF1DE798B938BA48B2ED3. ↩︎

Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life, British Library MS Add 88897/1 (hereafter Book 1), pp.286ff; Alice Thornton, Book of Remembrances, Durham Cathedral Library (DCL), GB-0033-CCOM 38 (hereafter Book Rem), pp. 186ff. ↩︎

Benjamin Neudorf and Yin Liu, "Signes-de-Renvoi", ArchBook: Architectures of the Book (2016), https://drc.usask.ca/projects/archbook/signes_de_renvoi.php. ↩︎

Kwakkel, Books Before Print, 47, notes how space for margins had to be planned before writing the manuscript book could even begin. ↩︎

Alice Thornton, Book 3: The Second Book of My Widowed Condition, British Library MS Add 88897/2. ↩︎

See, for example, Harold Love, Scribal Publication in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993); Peter Beal, In Praise of Scribes: Manuscripts and Their Makers in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford, 1998); Mark Bland, A Guide to Early Printed Books and Manuscripts (John Wiley & Sons, 2013). ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Sharon Howard. 'At the Margins of Alice Thornton's Books'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2023-07-10-at-the-margins/