Encoding Alice Thornton's Books

Encoding highly complex texts like Alice Thornton's books is a process of interpretation in order to make explicit some of the underlying structures and patterns in a text. How does text encoding in TEI XML enable our project to turn Alice Thornton's books into a digital scholarly edition and help to answer our key questions?

Text encoding: what is it for?

In the words of the Women Writers' Project, “text encoding is a process of transforming a source into data, using markup”.[1] Markup in effect embeds data directly into a text (by means of tags surrounded by < and > signs), which a computer can recognise and process in various ways, while still being (just about) readable by humans.

The Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) XML schema is not the only possible option for a project like ours. But it's widely used to create digital editions of historical texts and Alice Thornton's Books has chosen it for several reasons, not least:

- its focus on the meaning of text before appearance

- it's been designed by and for the research community

TEI has evolved over three decades to cover most of the possible needs of a project like ours straight out of the box (and it can be customised further). If I have a problem, it's very likely that I'll be able to get help from the TEI community online. Also, using a well-known and well-documented standard schema will make it much easier for future projects to take our work and re-use it in ways we might not have anticipated.[2]

Alice Thornton's books have multiple potential audiences - in literature and history (social, political, religious, gender, of medicine) - and beyond academic readers (e.g. those interested in the British Civil Wars, local history, family history, women's history). Because we can mark up several different “layers” of meaning within the texts, TEI makes it possible, in a sense, to have multiple versions of the books within a single edition, catering for varying perspectives.

- Structural: the major divisions of texts such as front/back matter, main body, chapters, paragraphs

- Page layout: page and line breaks, running heads, marginalia

- Word/phrase: authorial deletions and insertions, expansion of contractions, sic, etc

- Contextual: dates; people and places; bibliographical (especially biblical) references; events

- Editorial annotations and modernisation

Order from chaos

As just one example, TEI includes elements to distinguish certain chunks of text as people's names in the “sea of words”.[3] But that's not quite enough on its own.

In a narrative text the same person might be mentioned in many different ways: below is a list of just some of the various ways that Alice referred to her son Robert. “Robert” or the nickname “Robin” are very frequent, but in almost half of all mentions she doesn't use his name at all. (There are some individuals whom Alice hardly ever calls by name, especially her parents.) Often the variations are tiny, but a computer will treat them as all different unless told otherwise. Conversely, there are several distinct individuals who share a name or other form of reference. There are eight other people whom Alice might refer to as “my child”, as well as several people named Robert, including another Robert Thornton.

Selected mentions of Robert Thornton

| text of mention | number |

|---|---|

| Robert | 8 |

| Robin | 8 |

| Robert Thornton | 5 |

| Robin Thornton | 4 |

| my deare Childe | 2 |

| his Person | 1 |

| my 7th childe | 1 |

| my child | 1 |

| my childe | 1 |

| my Childe | 1 |

| my deare & sweet Childe | 1 |

| my deare & sweete Childe | 1 |

Fortunately, TEI also has methods to link tagged elements (of all kinds) together. This enables us both to identify and link all the variants of the same person and to separate the ambiguous cases. We're creating project databases for people and places, which will in turn enable us to link them to other information, like the short biographies that Jo Edge has been writing, and even to external sources. We can use all of this to enrich the searching and browsing experience of users in the digital edition.

A case study

Systematic markup also enables quantitative analysis. For example, we're interested in the relationship between Book 1: The First book of My Life and the Book of Remembrances (Book Rem). They're very similar in many ways: they cover the same period from Alice's birth in 1626 to her husband's death in 1668, often using much of the same language. Moreover, they're divided into very similar chapters or sections, have much of the same front matter, an “index” (really a table of contents) and extra passages that Alice added at some time after the original text.

The most obvious difference between them is that the Book Rem is much smaller than Book 1, at only about 1/3 the word count. So we might speculate that Book Rem is a kind of first draft, or a “pocket-sized” edition.

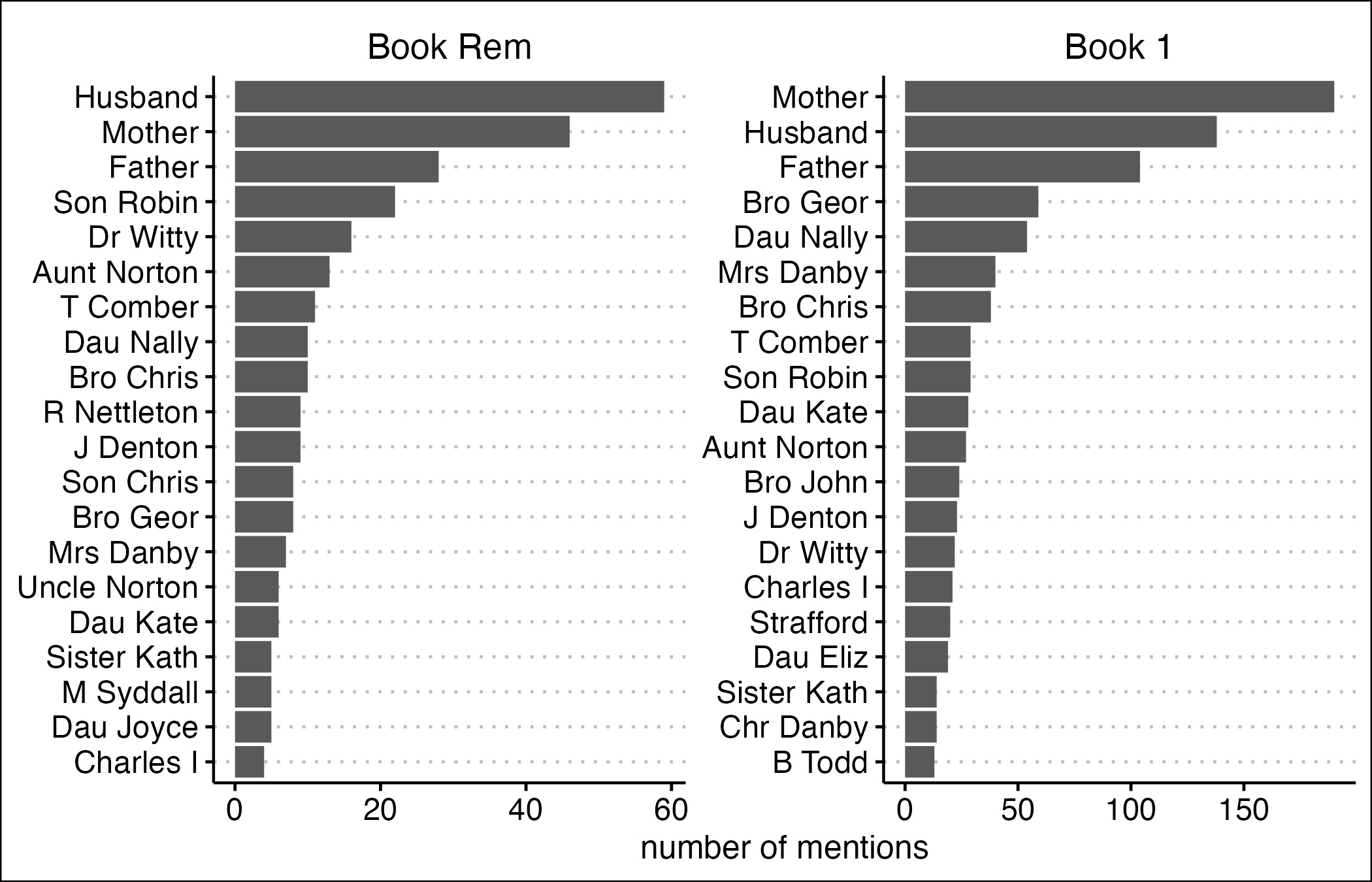

Here I'll explore just two elements of the markup of the two books, people and dates, beginning with a look at the 20 most frequently mentioned people in each book.

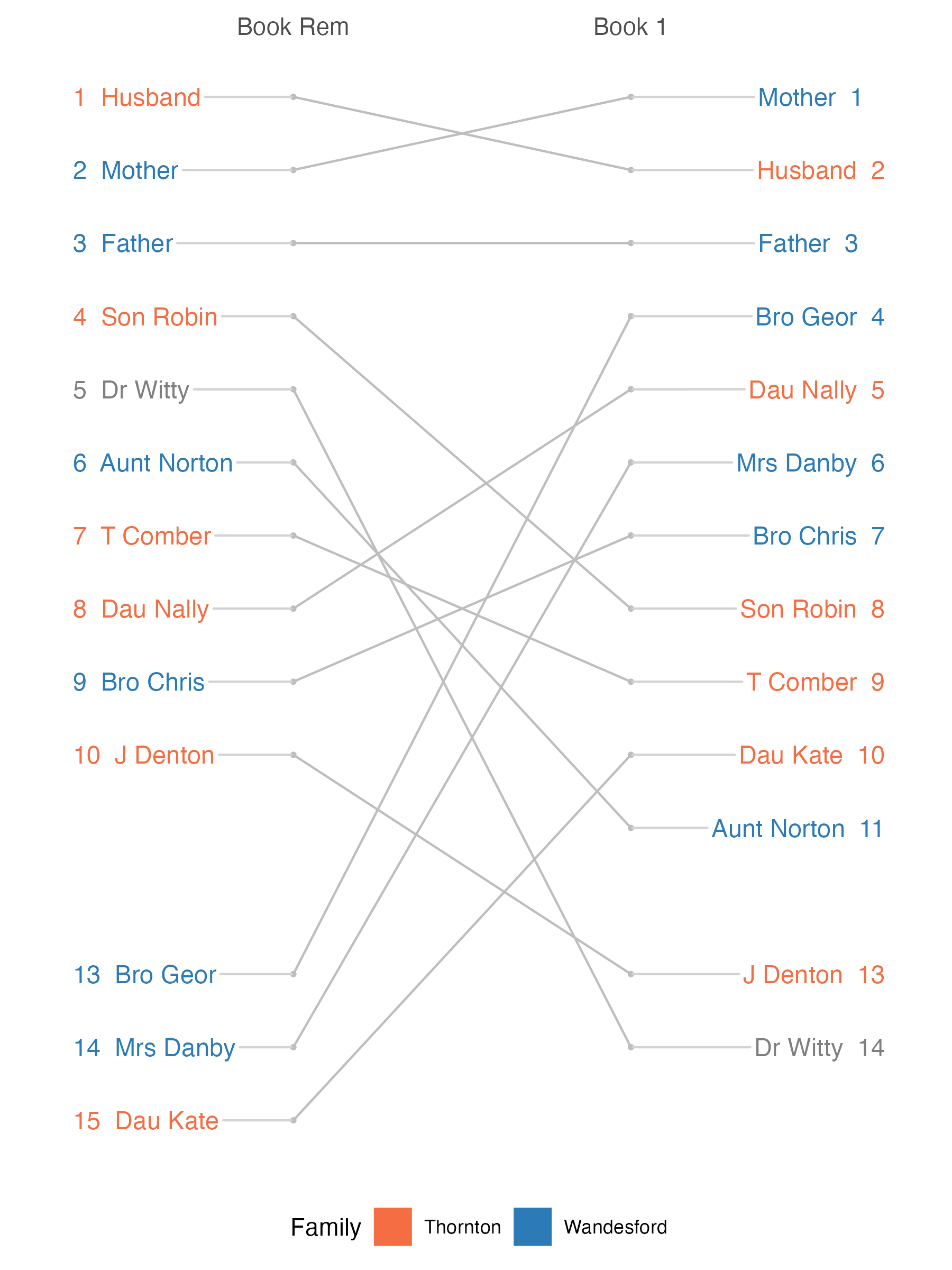

At first sight they do look broadly similar, with the same names in the top three. But on a closer examination, there are quite a lot of variations in rankings. It's easier to compare these changes with a less common type of chart (known as a slopegraph). In addition to comparing the rankings, I've colour-coded the names according to their family connection, Thornton or Wandesford (Alice's birth family):

Only seven people are in the top ten in both books. But more intriguingly, four of the six members of the Thornton family are mentioned more frequently in Book Rem than in Book 1 and, conversely, five of the six Wandesfords are mentioned more in Book 1 than in Book Rem.

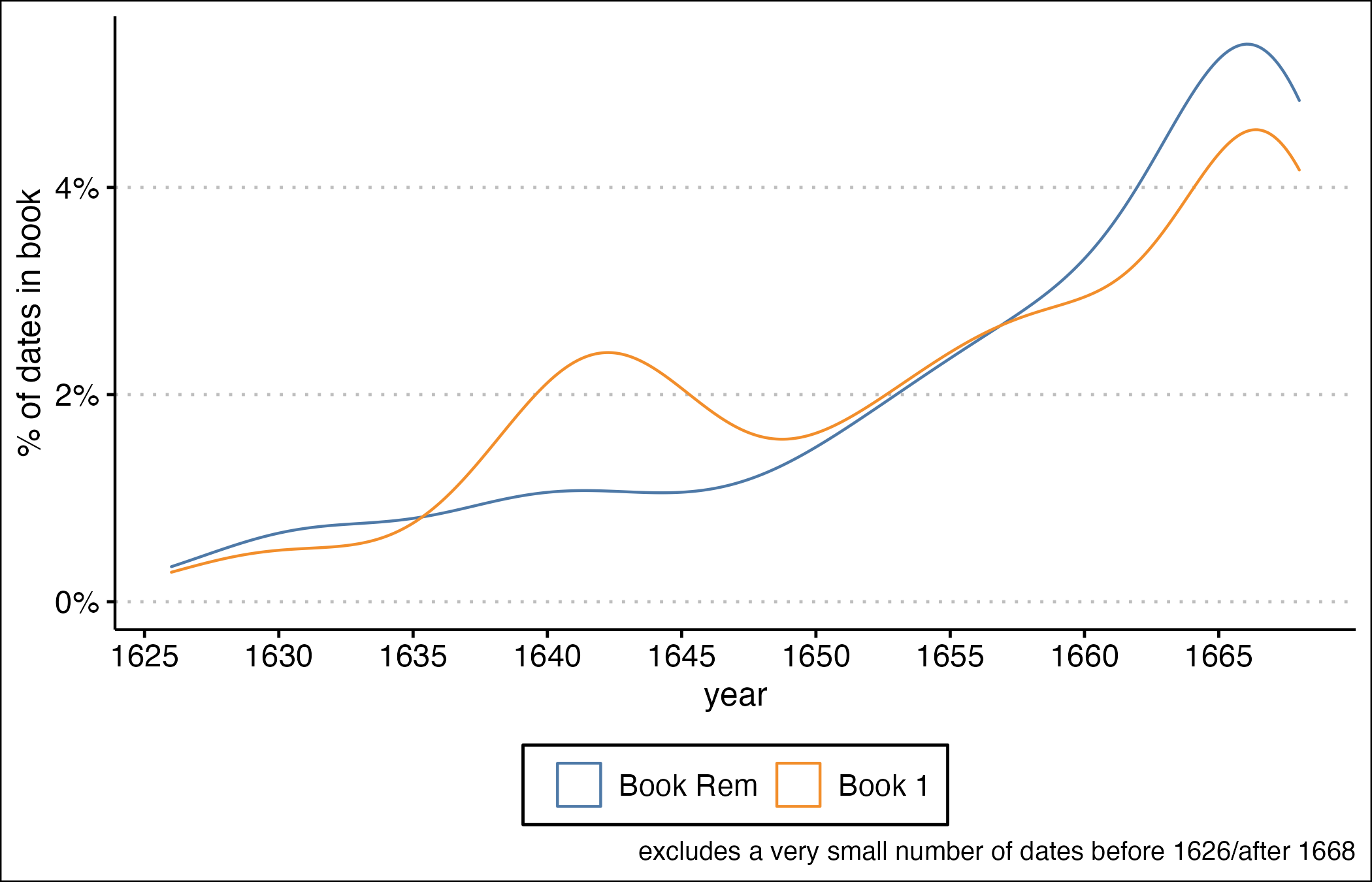

This is mirrored in the comparative frequencies of mentioned dates in the two books (it's important to remember that Alice married William Thornton in December 1651). This chart shows that the two books' coverage of Alice's early years and of the 1650s are quite similar; the big differences are for the 1640s and 1660s.

It's clear, then, that Book 1 is not simply a longer or more polished version of Book Rem. In Book 1, as Ray Anselment has noted, Alice's Wandesford family fortunes are much more significant.[4] She added a large amount of extra material about the series of traumatic personal and political events from her father's death in 1640, the Irish Rebellion, Civil Wars and Revolution and her brother's death in 1651. In Book Rem these are covered in brief entries that take up just 4 pages, and she focuses much more on her marriage, children and the death of her husband. One of the project's objectives is to deduce why Alice decided to expand her story of her life in the way that she did.

'What is Text Encoding?', in Women Writers Project Guide to Scholarly Text Encoding (2007). ↩︎

The official TEI P5 guidelines are a key reference. Andrew Dunning, Transcribing medieval manuscripts with TEI (2019), is a useful guide to many specific elements of manuscript encoding. ↩︎

Lou Burnard, 'Names and dates', in What is the Text Encoding Initiative? (2014). ↩︎

Raymond A. Anselment, '“My First Booke of My Life:” The Apology of a Seventeenth-Century Gentry Woman', Prose Studies 24, no. 2 (2001), 1–14. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Sharon Howard. 'Encoding Alice Thornton's Books'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2022-08-25-encoding-alice-thorntons-books/