Alice Thornton’s Heart: An Early Modern Emoji

One of the benefits of working with Alice Thornton’s original manuscripts is that we got to see that where later editors had written ‘heart’, Thornton herself had sometimes used the sign (or emoji) ♡.[1]

When Amanda Herbert came across a similar feature in Sarah Savage’s diary, written 1686-88, she thought this was a ‘unique’ feature, one which her later female descendants deliberately copied.[2] However, Thornton's surviving Books were begun earlier than this, with both the Book of Remembrances and Book 1 written by the end of the 1660s. And other evidence suggests that Thornton was not the first to use the ♡ as a shorthand either. For example, Suzanne Trill found that both the Earl and Countess of Eglintoun used this symbol when addressing each other as ‘sweet ♡’ in their letters of 1615 and Ciaran Jones found it used in a Scottish religious diary dating to c.1655.[3]

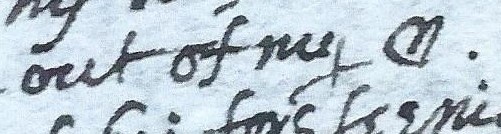

Across the four Books, Thornton uses this symbol on 67 different occasions, for a variety of purposes. It appears most frequently (41 times) as a symbol for her own heart, often at points of heightened emotion. For example, when her father, Christopher Wandesford, was on his deathbed, Thornton recalls that ‘his earnest look, did never go out of my ♡’.[4]

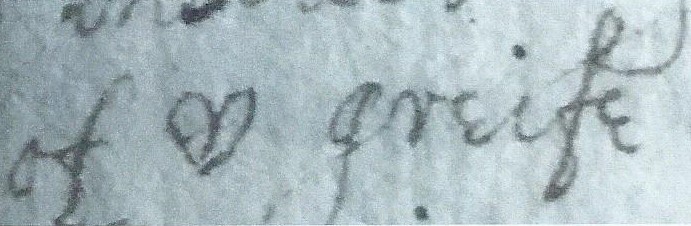

In later life, overwhelmed by the circulation of scandalous rumours about her that threatened to ‘be the ruin of my life,’ Thornton avers that, without the support of her beloved Aunt Norton, she ‘had undoubtedly perished with that heavy load of ♡ grief and sorrow’.[5]

Nevertheless, there are several instances in which the ♡ referred to is not her own, but that of another (most frequently that of her husband). There are also three occasions on which she uses ‘our ♡s’ to refer specifically to her and her husband’s marriage: ‘Thou, O Lord, having given us thy grace, uniting our ♡ s in that holy band of marriage wherein we lived’. [6]

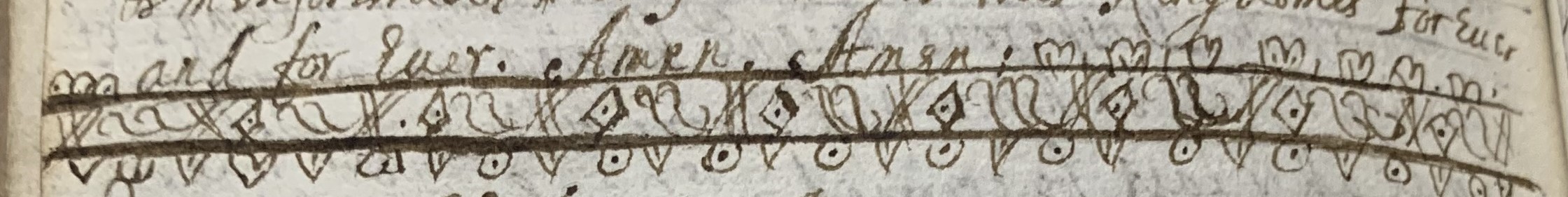

Thornton’s use of the ♡ symbol is not distributed evenly over the four volumes. While not all the references to Thornton’s own heart can be found in Book 1, the ♡ symbol appears there 41 times, which is by far the greatest number in any one volume.[7] Furthermore, Book 1 includes the most remarkable and extensive use of the ♡ motif in a perhaps unexpected context.

It appears repeatedly as part of a patterned border concluding her ‘Prayer and Thanksgiving for Deliverance from Destruction of the Kingdom, 1660’ that follows her celebration of the Restoration of the monarchy.[8] Within that ‘Prayer and Thanksgiving,’ Thornton also uses the heart symbol three times, with only one reference being to her own heart. The others metaphorically refer to ‘the ♡s and tongues of all faithful, loyal people in these kingdoms’.[9] Unusually, then, here Thornton’s use of the plural ‘hearts’ refers not to her actual husband but instead gestures toward the metaphorical marriage between the king and his people.

It is also worth noting that although the only autograph letter we have found from Alice Thornton to her husband, William, addresses him as ‘My dearest only Joy’, she used ‘for my dearest heart’ for the outer superscription. Perhaps the use of ♡ in this context was too familiar.[10]

When Charles Jackson compiled his edition in 1875, he had access to a further six letters in which - he tells us - Thornton addressed her husband as ‘My dear heart’, ‘My dearest heart’, or ‘Dearest Heart’.[11] Given that Jackson had silently replaced the ♡ symbol with the word ‘heart’ elsewhere in the edition, we wonder if that was also the case with some or all of these letters. For now, we can only speculate.

For example, where Thornton writes ‘the ♡s of all’, Jackson has ‘the hearts of all’ and where Thornton writes ‘a thankefull ♡’, Anselment has ‘a thankefull heart’: Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life, British Library MS Add 88897/1 (hereafter Book 1), 182, 137; Charles Jackson. Ed. The Autobiography of Mrs. Alice Thornton of East Newton, Co. York. Durham: Surtees Society, 1875, 127; Alice Thornton, My First Booke of My Life ed. Raymond A. Anselment (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 89. ↩︎

Amanda E. Herbert, Female Alliances: Gender, Identity, and Friendship in Early Modern Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 173. ↩︎

National Records of Scotland (NRS), GD3/5/115-117. Suzanne Trill, ‘Scottish Women's Letters in the Early Seventeenth Century’. Paper presented at the Cultures of Correspondence in Early Modern Britain, 1550-1640 conference (University of Plymouth, 14-16 April, 2011). NRS, GD237/21/64, fo. 12r (personal communication from Ciaran Jones, June 2019). ↩︎

The text quoted above is from our work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes: ‘his earnest look, did neur goe out of my ♡’. Alice Thornton, Book of Remembrances (hereafter Book Rem), Durham Cathedral Library (DCL), GB-0033-CCOM 38, 189. ↩︎

Original text: ‘be the Ruine of my Life;’ ‘had undoubtedly perished with that heavy load of ♡ greife & Sorrow,’ Book Rem, 131. ↩︎

‘Thou O Lord having given us thy grace uniting our ♡ s in that holy band of marriage wherein we lived,’ Book 1, 263. ‘Our ♡ s’ is used twice on this page and again in Book Rem, 127. There are also occasional references to the hearts of her sister, mother, daughter Kate and son Robert. ↩︎

It is used 17 times in BookRem, eight times in Alice Thornton, Book 3: The Second Book of My Widowed Condition, British Library MS Add 88897/2, and only once in Alice Thornton, Book 2: The First Book of My Widowed Condition, DCL, GB-0033-CCOM 7; that occurrence is quite distinctive as it appears in part of a quotation from a poem that refers to ‘mans ♡’, 7. ↩︎

Book 1, 186. ↩︎

Book 1, 183. ↩︎

Alice Thornton, ‘Letter to her Husband, undated (c. 1668)’, DCL CCOM 58/2. For an explanation of the distinction between the use of the superscription and the internal address to the reader, see ‘The Parts of a Letter.’ Bess of Hardwick’s Letters: The Complete Correspondence c. 1550-1608, edited by Alison Wiggins, et al. University of Glasgow, web development by Katherine Rogers, University of Sheffield Humanities Research Institute (April 2013). Accessed 8 Feb. 2023. ↩︎

Jackson, Autobiography, 291-6. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Cordelia Beattie, Suzanne Trill. 'Alice Thornton’s Heart: An Early Modern Emoji'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2023-02-13-AliceThorntonsHeart-Blog/