'A Curious Account': Alice Thornton on the Last Days of Charles I

We are nearing the anniversary of the execution of Charles I, which took place on 30 January 1649. For Alice Thornton, looking back on this c.1669 when writing Book 1: The First Book of My Life, Charles I was a 'martyr' who was 'cruelly murdered by the hands of blasphemous rebels, his own subjects, at Whitehall, London, the 30th of January 1649'.[1] Alice was from a royalist family, the Wandesfords, and maintained this allegiance, even though the man she married in 1651, William Thornton, was more ambivalent about the monarchy.

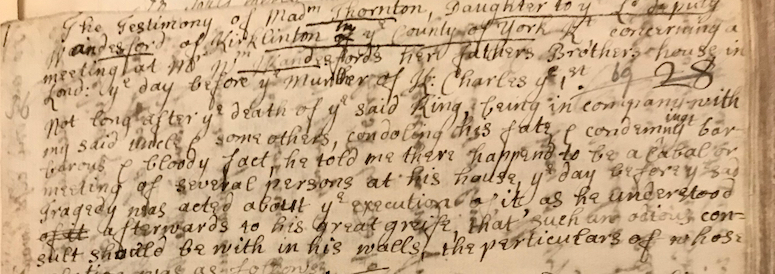

But Thornton, in other writings, had more to say about the final days of Charles I. She gave an account of a meeting, that took place at her uncle William Wandesford's house in London, between Charles I and a number of men who sought to persuade the king to acknowledge the justice of the high court's proceedings in order to avoid execution. She claimed that this was the day before he was sentenced to death which would make it 26 January 1649. Her account was seen as noteworthy by contemporaries but cannot be verified by other sources, with one recent scholar sceptical about its veracity.[2]

Charles Jackson in 1875 called this 'a curious account ... now lost', which he accessed from a note in the 1799 edition of the Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Thomas Comber, DD, her son-in-law, by another descendant.[3] However, the account, virtually verbatim, does survive in a letter dated 10 May 1710, five years after Thornton's death. The letter is from George Paul, Vicar-General to the Archbishop of Canterbury to Dr Cox Macro, clergyman and antiquarian, and Paul notes that 'your fellow Collegian Laurence Eachard' wanted it 'in order to be mentioned in his History'.[4]

Echard did indeed include it in volume 2 of his History of England (1718), noting that 'I have received from a good friend a manuscript testimonial of Mrs Thornton, a Yorkshire gentlewoman, daughter to Sir Christopher Wandesford, who had been Deputy Governor of Ireland under the Earl of Stafford... The person was generally esteemed for her worth and piety and has given this following account, worthy of the reader's notice'.[5]

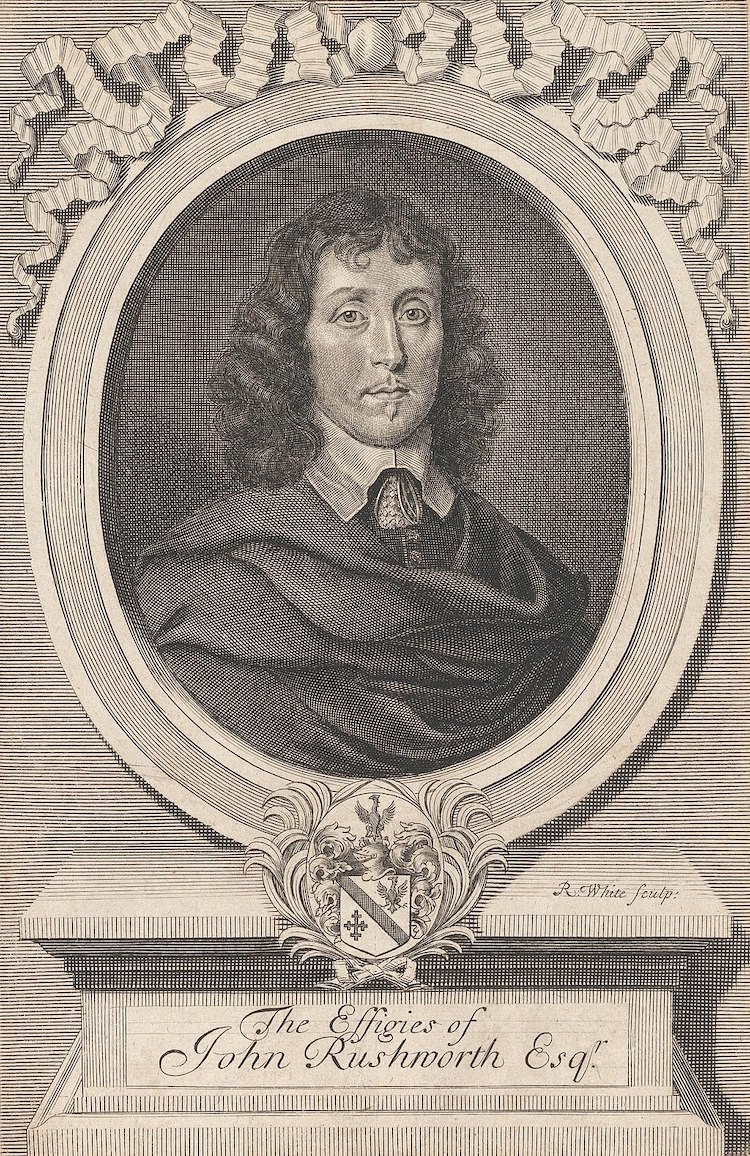

Part of what makes the account so 'curious' is the named people said to be at the secret meeting with Charles I. According to Thornton's account, 'Mr Rushworth (author of the Collections)' had asked to use the room, 'some days before'. On the day:

There were about 12 of them, he [William Wandesford] saw several disguised faces, particularly the Lord Baltimore and Mr William Lilly, and others suspected by him to be papists, which strange mixture did much amaze him.[6]

John Rushworth, author of the Historical Collections (1659), had strong ties to the parliamentarian cause.[7] After the Restoration, he was summoned to the House of Lords on 24 July 1660 to answer the question, 'What he knows of a Meeting of Twelve Persons, at The Beare of the Bridge Foot, concerning the Contrivance of the King's Death?'. Rushworth denied knowledge of that meeting but did admit knowing that some men were discussing a trial.[8]

Although Thornton's account refers to 'papists' in the plural, the only Catholic to be named is Lord Baltimore: Cecil Calvert, second Baron Baltimore, announced his family were converting to Catholicism c.1624. Lord Baltimore's colony in Maryland was at risk of being taken over by parliament and so his presence might help account for the reference to the 'strange mixture' of people in attendance.[9]

The third named man was William Lilly, an astrologer. He had published a pamphlet, A Prophecy of the White Kings Dreadfull Dead-Man Explaned (1644), which predicted the end of the Stuart monarchy and implied the violent death of Charles I, who he accused of engaging in 'an uncivil and unnatural war against his own subjects'.[10] When Lilley wrote his own memoirs, first published in 1681, he did not mention the meeting at Wandesford's house but noted that he attended the trial of Charles I one day, saw Rushforth there, and felt the questioning by the judge was 'audacious' and that the king 'replied with great magnanimity and prudence'.[11]

Echard included Thornton's account in his history as an example of those who were deeply involved in the condemnation of Charles I 'but acted with more privacy and behind the curtain', noting also that 'most of the actors seemed still to have had some inclination to save the king's life, if they could have had some terms of security'.[12] Thornton makes clear that her uncle knew nothing of the nature of the meeting until after Charles I was executed: 'he understood afterwards to his great grief, that such an odious consult should be within his walls'.[13]

The text quoted above is from our work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes. Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life, British Library (BL) MS Add 88897/1, 94: 'was cruelly Murthered, by the hands of Blasphemous Rebells, his owne subjects, att White hall. London the 30th of Janueary: 1648'. Thornton uses Lady Day dating here. ↩︎

Joad Raymond, 'Rushworth [Rushforth], John (c. 1612--1690), historian and politician.' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004. Accessed 16 Dec. 2022. ↩︎

Charles Jackson. Ed. The Autobiography of Mrs. Alice Thornton of East Newton, Co. York. Durham: Surtees Society, 1875, 347; Thomas Comber. Ed. Memoirs of the life and writings of Thomas Comber (1799). Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). Accessed 15 Dec. 2022. ↩︎

George Paul, 'Letter to Dr Macro.' BL Add 32556, 69-70. The 1799 version has a few additions, the most noteworthy being that the account was signed by Thornton. ↩︎

Modernised from Laurence Echard. The history of England. From the first entrance of Julius Cæsar and the Romans, to the end of the reign of King James the first. 2nd ed., vol. 2, printed for Jacob Tonson, 1718. ECCO. Accessed 15 Dec. 2022. ↩︎

Modernised from Paul, 'Letter to Dr Macro.' 69. ↩︎

Raymond, 'Rushworth [Rushforth], John.' ↩︎

'House of Lords Journal Volume 11: 24 July 1660,' in Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 11, 1660-1666, (London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1767-1830), 104-105. British History Online. Accessed 16 Dec. 2022. ↩︎

Francis J. Bremer. 'Calvert, Cecil, second Baron Baltimore (1605--1675), colonial promoter.' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004. Accessed 16 Dec. 2022. ↩︎

Patrick Curry. 'Lilly, William (1602--1681), astrologer.' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004. Accessed 16 Dec. 2022. ↩︎

Charles Burman and Thomas Davies. Eds. The Lives of Those Eminent Antiquaries Elias Ashmole, Esquire, and Mr. William Lilly. 1774. 95. ↩︎

Echard. The history of England. Vol. 2. 641. ↩︎

Paul, 'Letter to Dr Macro.' 69. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Cordelia Beattie. ''A Curious Account': Alice Thornton on the Last Days of Charles I'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2023-01-27-last-days-charlesI/