Black Monday: The Solar Eclipse of 1652

Today, October 25 2022, there is a partial eclipse of the sun. However, a much fuller solar eclipse took place on Monday 29 March 1652, which cast complete darkness over Scotland and much of northern England.[1] It was such a memorable and terrifying event that it was known as 'Black Monday' for years to come.

A newly-married and pregnant Alice Thornton, living at Hipswell Hall in the North Riding of Yorkshire, described her experience of this eclipse in Book 2: The First Book of My Widowed Condition:

At which time I was big with child and the sight of it much affrighted me, it being so dark in the morning at breakfast time and came so suddenly on us that, in a bright sunshine morning, he [i.e. William] could not see to eat his breakfast without a candle. But this did amaze me much and I could not refrain going out into the garden and look on the eclipse in water discovering the power of God so great to a miracle, who did withdraw his light from our sun so totally that the sky was dark, and stars appeared, and a cold storm for a time did possess the earth. Which dreadful change did put me into most serious and deep consideration of the day of judgement which would come as sudden and as certainly upon all the earth as this eclipse fell out, which caused me to desire and beg of his majesty that he would prepare me for this great day in repentance faith and a holy life for the judgements of God was just and certain upon all sins and sinners.[2]

Writing later, no earlier than 1669, this is an account penned with hindsight, which is an important factor in considering the providential framework within which Thornton discusses the eclipse. The language she uses to describe the experience is deeply emotive – words such as 'affrighted', 'amaze' and 'dreadful'. She regarded the eclipse as a miracle from God and saw it as a portent of the Day of Judgment, which God could bring to earth just as easily as he did the eclipse. It was a reminder of God's ultimate power, and that Christian men and women should be repentant and live good lives. Deeply religious Protestants like Thornton were extremely concerned with their own salvation after death and so it isn't a surprise that events like this were seen with such awe and dread.

On a more practical note, she viewed the eclipse in water - presumably because she knew that staring directly into the sun could potentially damage her eyes. Perhaps she had a pond in her garden, or maybe she filled a bucket. It was common knowledge that looking into eclipses could damage the sight, for example, Edward Pond gave some advice on how to 'behold an eclipse of the sun without hurt to the eyes' in his 1652 almanac:

Take a burning-glass, such as men use to light tobacco within the sun; or a spectacle-glass that is thick in the middle, such as is for the eldest sight; and hold this glass in the sun as if you would burn through it a pasteboard or white paper book, or such like; and draw the glass from the board or book, twice so far as you do to burn with it: so by direct holding it nearer or further, as you shall see best, you may behold upon your board, the round body of the sun, and how the moon passes between the glass and the sun during the whole time of the eclipse.[3]

Portents, Providence and the Political Landscape

Alice Thornton was not the only person in seventeenth-century England who believed that unexpected, bizarre and scary events were portents of things to come. Eclipses were particularly frightening omens. As Alexandra Walsham points out, 'monstrous births, blazing stars, frightening apparitions, and eclipses were widely acknowledged to be providential tokens of future misfortune, and contemplated with a mixture of anxiety, astonishment, and awe'.[4]

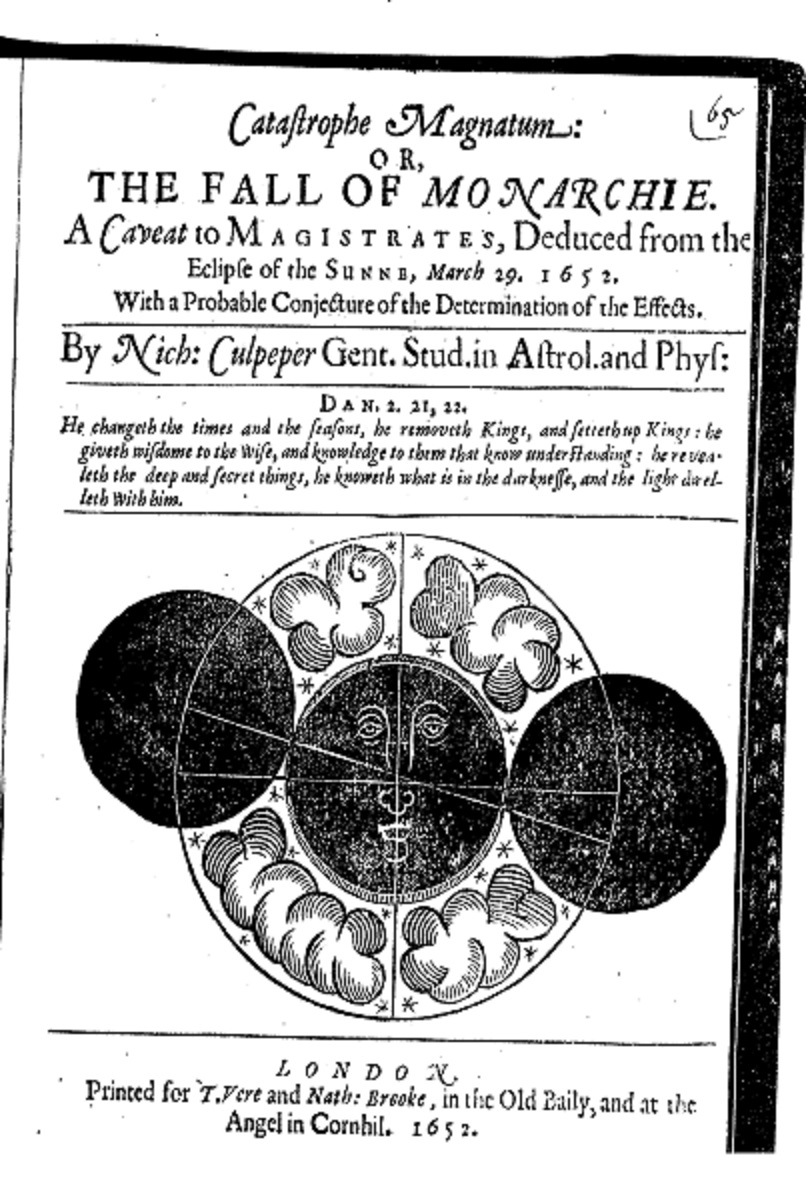

The title of astrologer Nicholas Culpeper's (1616-54) volume on this momentous event leaves little doubt as to his thoughts on the eclipse: Catastrophe magnatum, or, The fall of monarchie. Culpeper made predictions from this eclipse for many nations, but this is what he said about England:

Thou will in the year 1653 be molested with a consuming pestilence, and troubles, with a change of government at one and the same time, make thy choice wisely, God will have his own government established in thee, whether thou will or no; and tell me one thing, and tell me truly, whether is it fit he should have his will, or thee thine?[5]

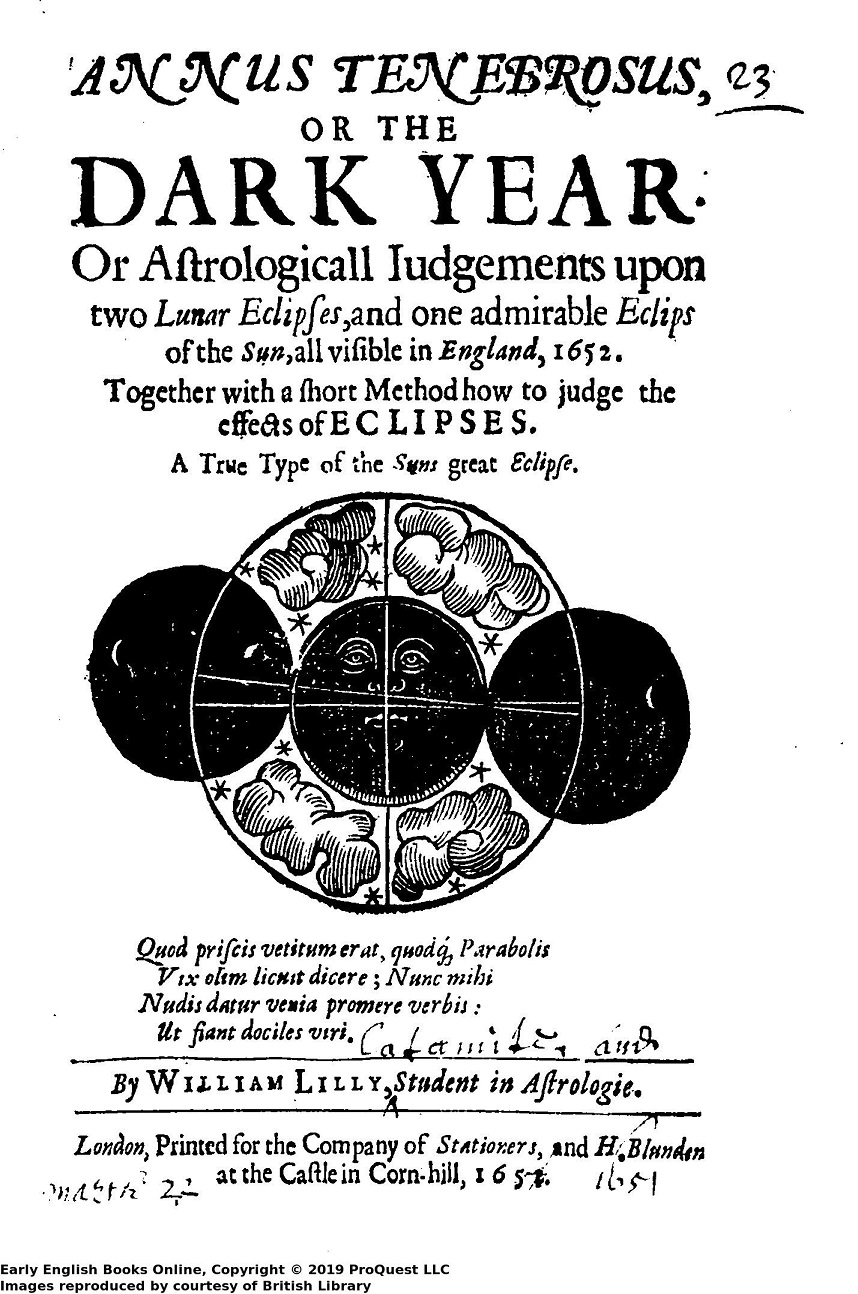

Another astrologer, William Lilly (1602-81), dedicated his almanac Annus Tenebrosus ('The Dark Year') to this solar eclipse, plus the two lunar eclipses of 1652 and 1653. Lilly foretold alarming events for England at sea: naval attacks by the Dutch, shipwrecks, piracy, theft, and storms. He also noted potential religious and political change, suggesting that Catholicism might be the cause of the restoration of the monarchy to England, via a Scottish king.[6] Unlike Thornton, Lilly wasn't producing this volume years later – it was published in 1652. But the predictions he made were relevant to the politico-religious situation in England in the early 1650s. Lilly, after all, had a book to sell.

Just over three years before this eclipse, in 1649, King Charles I was executed and replaced with Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector. The 1650s was a decade of change, especially for those who had supported the king and in many cases had their lands sequestered by the State for doing so. Alice's family was no exception – her eldest brother George, heir to the Wandesford estate, had had his lands seized.

In 1652, Thornton herself was also in a state of great change. She had married in 1651, precipitated by the problems with the Wandesford lands and the subsequent death of her brother George. The eclipse happened when she was pregnant for the first time - although not as heavily as her account makes out; her first child, a daughter, was born in August and lived only thirty minutes after she was born. It is no wonder that Thornton regarded the eclipse as a portent which made her think upon the Day of Judgment and, writing much later and knowing what would become of that first pregnancy, felt it fitting to note down such an omen.

29 March is the Julian calendar dating used by Thornton; the modernised date is 8 April. ↩︎

The text quoted above is from our work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes. 'At which time I was big with Child & the sight of it much affrighted me. it beeing soe darke in the morning at breakfast time & came soe sudainly on us that in a bright sun shine morning That he could not see to Eate his breakfast with out a Candle Butt this did amaze me much & I could not Refraine goeing out into the Garden & loole on the Eclips in water discovring the Power of god soe great to a miracle who did with draw his Light from our Sun so totally that the sky was darke & starres appeared & a cold storme for a time did Posses the Earth. Which dreadfull Change did putt me into most serious and deep consideration of the day of Judgmt which would come as sudaine & as certainly uppon all the Earth as this Eclips fell out, which caused me to desire & beg of his majesty that he would prepare me for thes great day in Repentance faith and a holy Life for the Judgements of God was just & Certaine uppon all sinns & Sinners', Alice Thornton, Book 2: The First Book of My Widowed Condition, Durham Cathedral Library, GB-0033-CCOM 7, 136-137. ↩︎

Modernised from Edward Pond, An Almanack for the year of our Lord God 1652 (Cambridge, 1652), sig. C1v, cited in Anna Marie Roos, 'Annus Tenebrosus: Black Monday, faith and political fervour in Early Modern England’, in Eclipse & Revelation: Total Solar Eclipses in Science, History, Literature, and the Arts ed. Tom McLeish and Heinrike Lange (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). ↩︎

Alexandra Walsham, Providence in Early Modern England (Oxford University Press, 2001), 167. ↩︎

Modernised from Nicholas Culpeper, Catastrophe magnatum, or, The fall of monarchie a caveat to magistrates, deduced from the eclipse of the sunne, March 29, 1652, with a probable conjecture of the determination of the effects (London, 1652), 69. ↩︎

William Lilly, Annus tenebrosus, or The dark year Or astrologicall iudgements upon two lunar eclipses, and one admirable eclips of the sun, all visible in England, 1652. Together with a short method how to judge the effects of eclipses (London, 1652), 32, 35. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Joanne Edge. 'Black Monday: The Solar Eclipse of 1652'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2022-10-25-black-monday-solar-eclipse-1652/