Alice Thornton and the Irish Rebellion of 1641

This guest blog to mark the anniversary of the Irish Rebellion is by Naomi McAreavey, Associate Professor in Renaissance Literature at University College Dublin. Naomi McAreavey is editor of The Letters of the First Duchess of Ormonde (2022) and, with Julie A. Eckerle, of Women’s Life Writing and Early Modern Ireland (2019). She is writing on Alice Thornton and Ireland for our in progress collection of essays for Amsterdam University Press.

CN: contains graphic description and artistic representation of scenes of massacre.

The time of the rebellion's discovery is near ... for which, sir, both you and I have cause to return our most humble gratitude to almighty God who did deliver us from the dreadful murders prepared for us when we were in Ireland by those horrid rebels. The Lord sanctify our hearts to be instruments to his glory.[1]

So wrote Alice Thornton in a letter to her brother in October 1677, evoking their shared memory of being in Ireland when rebellion broke out on 23 October 1641.

The rebellion began when a group of disaffected Irish Catholic lords conspired to seize some key strategic strongholds in Ireland. They failed to achieve the primary goal of taking Dublin Castle, however, and the revolt was initially confined to Ulster where Sir Phelim O'Neill had captured Charlemont fort in County Armagh. The rebellion gradually spread across the country during the winter months as Protestant settlers were robbed and ejected from their lands. During this time, thousands of refugees fled to the relative safety of Dublin or left the country altogether.

Alice was a young girl at the time of the rebellion; by the time she wrote her letter to her brother, she was a woman of middle age. As she utilized their shared trauma in Ireland as a theme for devotional practice, Thornton adopted a three-pronged approach that provides a template for the representation of Irish rebellion experiences in her Books:

- She focuses on the failure of the rebels’ plot to seize Dublin Castle rather than their success in seizing key strongholds in Ulster.

- She emphasizes thankfulness for her deliverance from rebel violence rather than dwelling on the violence endured by the British Protestant community.

- She interprets personal and communal experiences of the rebellion through the lens of divine providence.

Thornton’s providential framework was rooted in the belief that God’s guiding hand is always at work in the world. And she was far from unique in understanding her suffering and deliverance in October 1641 as part of a divine plan. October 23 had been observed as an annual day of thanksgiving in Ireland since 1661; the Church of Ireland version of the Book of Common Prayer (1666) included prayers to be said at the service.[2] The emphasis on divine deliverance in these prayers through ‘thy most wise and ever watchful Providence’ aligns with how Thornton made sense of the rebellion in providential terms.[3]

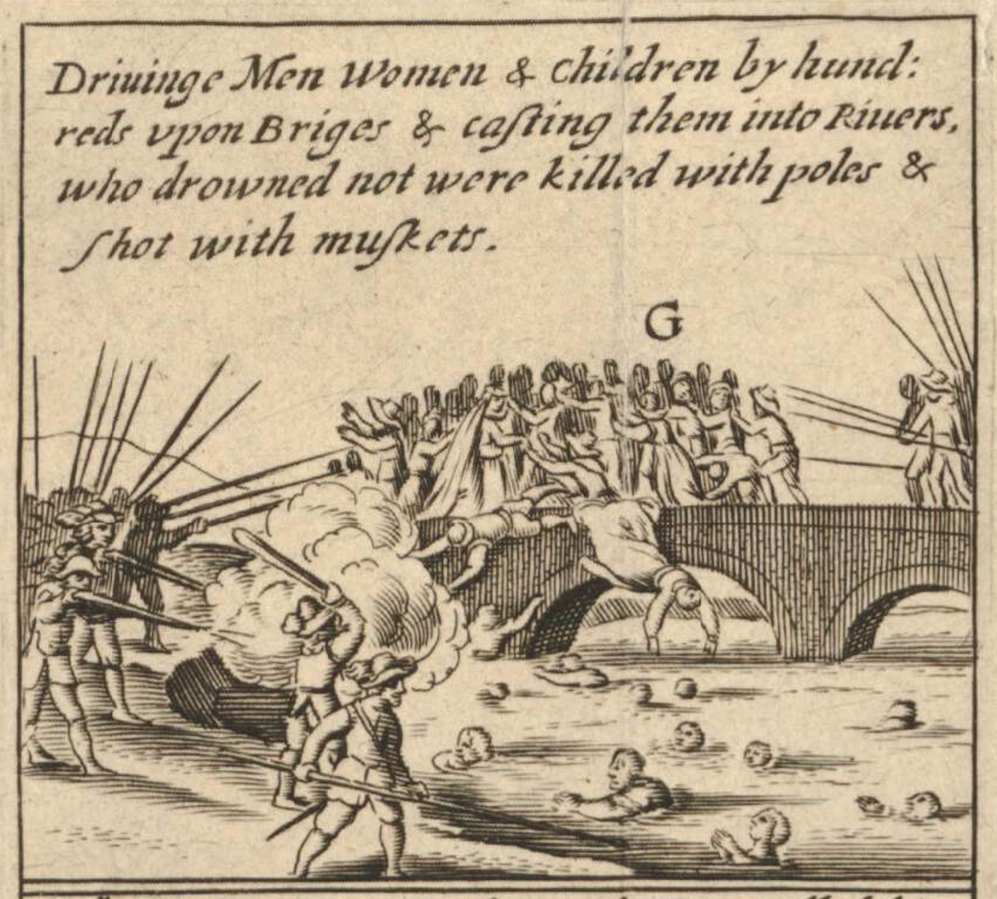

The 23 October thanksgiving recalled the rebellion as a massacre of English and Scottish settlers by the Irish rebels. The divine service acknowledged how God ‘didst suffer those men of blood to make their swords fat with the slaughter of so many thousand Innocents’.[4] This was the version of events established by Sir John Temple’s influential and often-reprinted Irish Rebellion.[5] Temple’s version also seems to have shaped the way Thornton represented the rebellion. When in Book 1 she remembered ‘the many thousands that perished to be murdered, stripped, slain, burned, drowned’, she seemed to be drawing from Temple rather than her own witness.[6]

Alice was a fifteen-year-old girl living in Dublin with her recently widowed mother when the rebellion broke out. When news reached them, they sought refuge in Dublin Castle before returning to their own house to prepare to depart Ireland for good. When Thornton recalled this frightening time, she provided a catalogue of sufferings including ‘frights, fastings and pains (about sacking the goods, and wanting sleep, times of eating, or refreshment)’.[7] She recalled how these privations had such an impact on her ‘young bodie’ that she succumbed to ‘a desperate flux, called the Irish disease’ that was nearly fatal.[8]

In the meantime refugees were beginning to arrive in the capital, although Thornton said nothing of this. Temple wrote of ‘the daily repair of multitudes of English that came up in troops, stripped, and miserably despoiled, out of the North’.[9] They arrived in the capital ‘overwearied with long travel, and so surbated footsore, as they came creeping on their knees; others frozen up with cold, ready to give up the Ghost in the streets: others overwhelmed with grief, distracted with their losses, lost also their senses’.[10]

By December 1641 a commission was established in Dublin to collect the sworn testimonies of these refugees. The testimonies, known collectively as the 1641 Depositions, are a significant source of women’s voices from early modern Ireland. They include over 800 depositions by women from different ethnic, religious, and socio-economic backgrounds, and different ages, literacy levels, and family statuses. These women’s depositions provide a fascinating context in which to read Thornton’s account of the 1641 rebellion.

Comparing Thornton’s recounting of Irish rebellion experiences with those of the female deponents, it is apparent just how different hers is from theirs. While the deponents emphasised their agency and resilience even as they endured terrible trauma, Thornton stressed her passive suffering. By representing herself in terms of silent and passive Protestant victimhood, Thornton’s approach is therefore much more aligned with Temple’s brand of Protestant polemic.

Placing Thornton’s writing in the context of other Irish rebellion texts offers a glimpse into how she wrote about the 1641 rebellion and perhaps other aspects of her life story – less from personal experience and more from the reading of liturgy and history.

'The time of the Rebellions discovery is neare ... for which Sir both you & I have cause to returne our most humble gratitude to Almighty God who did delivr' us from the dreadfull murders Prepared for us when we weere in Ireland by those horrid Rebells. The Lord sanctifie our hearts to be instrumts' to his glory'. Letter from Alice Thornton to her brother, Christopher Wandesford, 9 October 1677. National Library of Ireland, Dublin, Ormond Papers MS 2368 (Volume 68, 171). ↩︎

Church of Ireland, The Book of Common Prayer (Dublin, 1666), 231-34. ↩︎

Book of Common Prayer, 231. ↩︎

Book of Common Prayer, 233. ↩︎

Sir John Temple, An History of the Irish Rebellion (London, 1646). ↩︎

The text quoted above is from our work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes: 'The many 1000ds that perished. to be murdered, stript, slaine, burned, drowned’. Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life (hereafter Book 1), 68. ↩︎

'Frights, fastings & paines about sacking the goods, & wanting sleepe, times of eating, or refreshment': Book 1, 66. ↩︎

'A desperate flux. called the Irish disseas’: Book 1, 66. ↩︎

Temple, Irish Rebellion, 106. ↩︎

Temple, Irish Rebellion, 106. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Naomi McAreavey. 'Alice Thornton and the Irish Rebellion of 1641'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2023-10-23-mcareavey-rebellion-1641/