Digital Edition: Where will our new release take you?

We are delighted to announce the digital release of a further 81 pages of the Book of Remembrances. With half of this book now available to browse, we’d love to hear your comments on the text and the digital edition. It’s there for you to discover, and we’d also like to know which of Alice Thornton’s recollections speak to you.

Eleanor Thom is a writer of fiction who works in the Thornton’s Books team as our Engagement and Impact Officer. She has picked five passages from the newly released pages. These are incidents recorded by Thornton, or words that struck a chord and made Eleanor curious to find out more.

There are so many ways to read the autobiographical writing of Alice Thornton. Some of her words resonate over many centuries, when I can relate to her as a writer, or a woman, or a mother. Other passages made me curious and some made me laugh. What I also encounter in Thornton's writing are clues, ways into the past that are ripe for further research. As any historical writer will attest, it’s hard to resist the allure of a rabbit hole, the potential for a peek into Thornton’s world. The events I've picked out all set me off on a path to finding out more.

A Blaze on St Martin's Lane

Alice was just six years old when servants rescued her from a fire:

There was a great fire in the next house to my father’s, in St Martin’s Lane in London, which burned a part of our house and had like to have burned our house but was prevented through the care of our servants. This was done at night when my father and mother was at court. But we were preserved in my Lady Leveson’s house, being carried by Sarah thither. This fire did seem to me as if the day of judgment was come, and caused great fear and trembling (p. 17).

Thornton shared both the emotion and the facts of the event. Knowing that she was living in St Martin’s Lane in London, I wanted to find out what this location was like in 1632. I found a list of her neighbours, who included Dutch painter Daniel Mytens and his second wife, the painter Susanna Droeshut. There is a portrait of this couple by Anthony Van Dyck dated 1630, just two years before the fire Thornton remembers. Perhaps to a young Alice they were familiar faces.

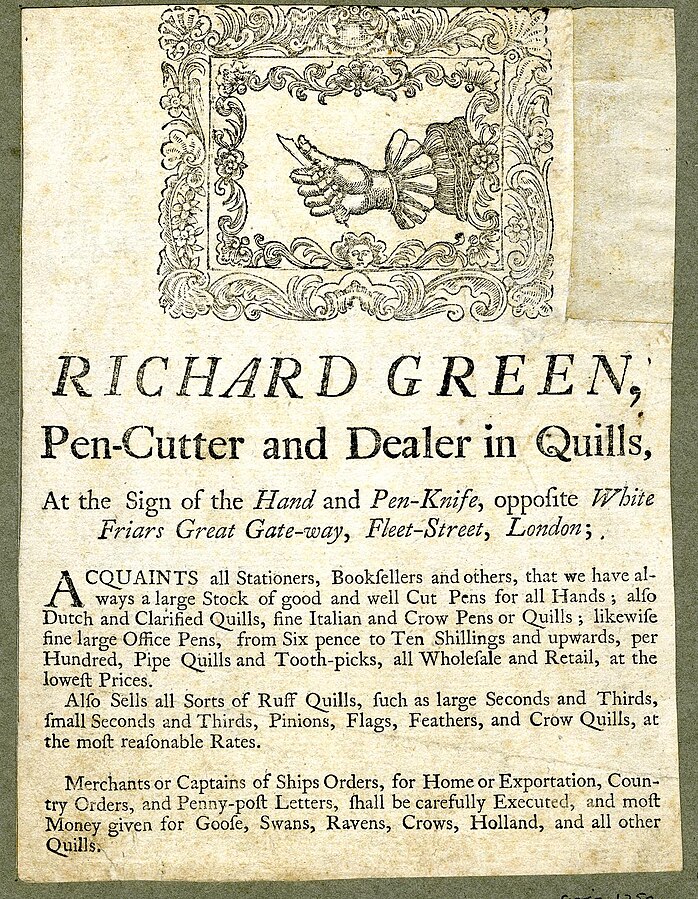

Penknives and Excision

CN: suicidal ideation

Sometimes a physical document is scarred by an event, and a story is told in more than words. Alice Thornton purchased six steers (young oxen) in 1662, and a heated argument ensued between her and her husband William (p. 55). A section of a page is missing here, cut away. This uncharacteristic deletion has a violence about it, and it could have stayed a mystery were it not for Thornton referring back to the incident, saying that it was the devil which tempted him (William) against them both (p. 58).

Thornton imagined blood on William’s penknife as he threatened to take his own life, and she was afraid for herself and for her unborn seventh child. It is a shocking account.

A Mark on the Heart

Thornton was pregnant with Robert when the incident above took place. He survived into adulthood, but Thornton remembered that for a long time he carried a mark on his chest. She took this as a reminder of God’s mercy, saving them from harm at the hands of William when he was not well. Robert’s heart-shaped mark eventually faded into a ‘T’ shape, and according to Thornton it later vanished altogether. The stages the mark went through are described in intricate detail in Thornton's account, written some years later. This is my own imagination at play, but I felt these passages spoke to something inside Thornton that was much more permanent.

He did, I believe, set a mark upon my son Robert’s heart for a note of his deliverance at that time. For, when the child was born, he had a very strange mark, just upon his heart, of sprinkles of blood, pure and perfectly distinct round spots, like as if it had been sprinkled upon his skin and the white perfectly appearing betwixt them and in the midst thereof, as if it had been cut with a knife, a longish cut (p. 61).

Chamomile Cure

Many passages in Thornton’s writing deal with the body, illness and death. In the Book of Remembrances, the passing away of extended family members including an uncle who ate too much cold melon, are placed in a list along with the beheading of King Charles I. They occurred around about the same time, and are given equal weight. Thornton dedicated much longer passages to other bereavements, such as the death of her mother. Describing her mother’s final illness, Thornton mentioned using a common calmative still familiar today:

these stitches continued about 14 days, with the cough hindering her from almost any sleep. When, upon the use of bags with fried oats, butter and chamomile chopped laid to her sides, the stitches removed, and the cough abated as to the extremity thereof (p. 33).

Floods, Stitches and the Breeding of the Teeth

Some turns of phrase Thornton used to describe the body and its pains are unusual to our ears, and for me this is part of what makes her work so enjoyable. Her language can be very evocative. Thornton described the poor health of her daughter Nally after she started vomiting in bed. The focus is not just on this night of sickness, caused by eating bad fish, but Nally’s worrying health back to her earliest infancy. It’s a relatable amplification of Thornton’s alarm at having a child take suddenly ill. The term ‘breeding of the teeth’ makes teething sound like it was a particularly torturous process for poor Nally.

Blessed be the most gracious mercy of my God for ever that hath raised this child up from death very often, even from a young child being often in sounds upon the breeding of her teeth: this fit was June 13th, 1665, at Newton. When she was ill, she was even ravished with the glorious sight (p. 103)

The Alice Thornton’s Books project invites everyone to delve into the seventeenth-century words of Alice Thornton. You can read the newly released pages of Alice Thornton’s Book of Remembrances now, in modernised and semi-diplomatic versions.

We would love to hear about what you discover! Please get in touch via our socials.

Citing this web page:

Eleanor Thom. 'Digital Edition: Where will our new release take you?'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2023-09-15-digital-edition-eleanor-picks/