Taking it to Heart: Grief and Illness in Alice Thornton's Books

Content note: miscarriage, child illness

In February 1655, Alice Thornton was in bed recovering from giving birth to her second daughter, Elizabeth (Betty), when her maid called out to her. Her one-year-old daughter, Alice (Nally), in her cot in the next room, was experiencing convulsive fits.

Her maid Jane Flower and the midwife Jane Rimer were acting to save Nally. The fits stopped and started. The physical and mental effect that this sudden grief had on Thornton was profound:

I, lying the next chamber to her, … did hear her when she came out of them [i.e., her fits] to give great shrieks and suddenly that it frightened me extremely. And all the time of this poor child's illness, I, myself, was at death's door by the extreme excess of those - upon the fright and terror came upon me - so great floods that I was spent and my breath lost, my strength departed from me and I could not speak for faintings and dispirited so that my dear mother and aunt and friends did not expect my life but were overcome with sorrow for me. Nor durst they tell me in what condition my dear Nally was in her fits, lest grief for her, added to my own extremity with loss of blood, might have extinguished my miserable life.[1]

Thornton experienced a flood (uterine bleeding), and the maids then moved Nally to a room further away, where her mother could not hear her cries and screams which were clearly putting her in mortal danger.

As well as the flood, the shock of the incident had made Thornton's milk dry up and she wasn't able to breastfeed her newborn daughter for two weeks. But the story didn't end there. Just as Thornton was able to breastfeed Betty again, Nally fell into convulsions once more. A maid ran to her, saying that Nally was dead or nearly dead. Once again the physical effect on Thornton was intense:

Which did so suddenly affright me, being weak as before, and this flood came down upon me as before, and they had much to do to get me carried safe into my bed again.[2]

Luckily, Nally once again recovered, according to Thornton, thanks to God.

Thornton here describes a process which might seem melodramatic to the modern reader. She experiences a sudden shock of grief, which leads to a huge flux in her humours (uterine bleeding and the drying up of her milk). She is close to death, according not only to herself but to others around her. But God steps in to 'deliver' her from this terrible fate. This is a process that Thornton describes throughout all four of her autobiographical books, always caused by a sudden shock. I want to try and place this process in the context of both Thornton's writings and late-seventeenth-century understandings of medicine and the body.

Betrayal and grief

The passion which causes the process Thornton describes is sudden grief. Thornton conceives of grief as being either caused by the endangerment or death of a loved one; or betrayal by someone close to her.

Thornton's husband William was not a financially prudent man, which led to some difficult situations for his wife. The big betrayal came two years before his death, in 1666, when Thornton discovered that William had cut her two surviving daughters Nally and Katherine out of their inheritance of the family property of Leysthorpe in order to pay off debts. This was a result of Thornton's nephew by marriage, Henry Best, whom she had trusted to look over her legal papers, convincing her that one settlement needed amending. In fact, he introduced a loophole which meant William could cut off her heirs without her consent, which he did. The effect on Thornton was once again profound:

the very grief I apprehended was so great at that time, on the discovery to me, that it did force me to that miscarriage which I had and long continued sickness by the excess of floods, which lasted a long time on me and mentioned in my first book.[3]

Both Henry and William had betrayed her so profoundly that it caused her to suffer a miscarriage and months of excessive uterine bleeding. To Thornton's mind, this was caused by sudden grief provoking an excess of humours which forced her body to expel the foetus. She remained unwell until the following February.

How can we explain these extreme near-death experiences as a reaction to grief? The answer lies in early modern understandings of the inner workings of the human body.

Early modern bodies

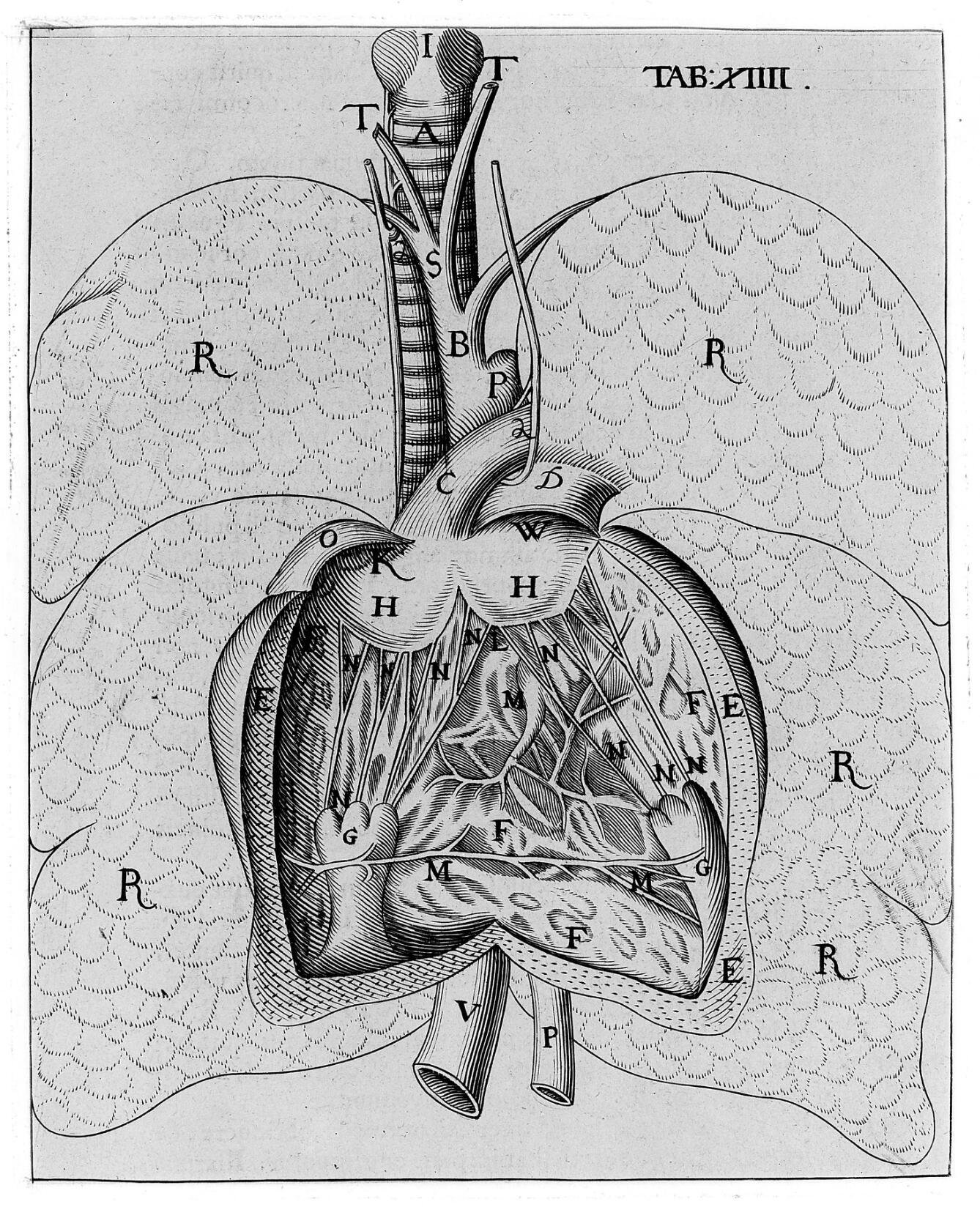

The organs, such as the heart, played an important role in bodily function in the early modern period. But, as Ulinka Rublack points out, what was really central here was the liquids that the organs processed - the four humours: blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm.[4] An excess of any one of these caused illness, so, it was understood that a flux of one of these from any orifice of the body was a way of restoring the balance. Like its medieval counterpart, early modern medicine was still very much based on the ancient medicine of Hippocrates and Galen.

According to Galenic thought, it was the six non-naturals that caused bodily humours to go into imbalance. These were air, food and drink, rest and exercise, sleep and waking, excretions and retentions, and mental affections - the passions. It is the last of these that concerns us here. The passions - what we would today call emotions - came under increasing scrutiny after 1500, most notably with Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621. The passions were a core part of this humoural system, not somehow separate from how the body functioned.

The concept of friendship, too, had undergone significant scrutiny in the century before Thornton. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) wrote that the main purpose of friendship was 'the ease and discharge of the fullness and swellings of the heart'[5] which was the base of all passions. So the opposite of friendship - betrayal by someone to whom you had quite literally opened your heart - was considered likely to cause a sudden and dangerous flux of humours.

Thus, Alice Thornton was not being melodramatic in these portrayals of her illnesses, but was describing a process that she understood her body to have undergone as a reaction to shock, which had put her in mortal danger. It is worth ending on Rublack's question: 'may it have been the case in the early modern period not only that bodily existence was conceived of differently from today, but also that this body actually behaved differently?'[6]

The text quoted above is from our work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes. 'I lieng the next Chambr to her and did heare her when she came out of them to give great Schrikes & sudainly that it frighted me extreamely, and all the time of this poore Childs illness. I my selfe. was att deaths dore by The extreame Excesse of those, uppon the fright & Terror came, uppon me, soe great floods that I was spent & my breath lost, my strength departed from me & I could not speake for faintings & dis-piritted soe that my d. mothr & Aunt & freinds did not expect my Life but over come with sorrow for me. Nor durst they tell me in what a condition my deare naly was in her fitts least greife for her added to my owe extreamity with losse of Blood might have have extinguished my miserable Life'. Alice Thornton, Book 2: The First Book of My Widowed Condition, Durham Cathedral Library, GB-0033-CCOM 7 (hereafter Book 2), 150-51. ↩︎

'Which did soe sudainly affright me beeing weake as before & this flood came downe uppon me as before and they had much to doe to gett me carried safe into my bed againe'. Book 2, 152. ↩︎

'the very greife I apprehended was soe great at that time on the discovry to me that it did force me to that miscarriage which I had & long contined Sicknes by the ex-cesse of floods which lasted a long time on me and ment-tioned in my first Booke'. Book 2, 275. ↩︎

Ulinka Rublack and Pamela Selwyn, 'Fluxes: the Early Modern Body and the Emotions', History Workshop Journal, 53, no. 1 (Spring 2002), 2. ↩︎

Francis Bacon, The Essays, ed. Jeremy Pitcher (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985), 139. Quoted in Rublack and Selwyn, 'Fluxes', 3. ↩︎

Rublack and Selwyn, 'Fluxes', 2. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Joanne Edge. 'Taking it to Heart: Grief and Illness in Alice Thornton's Books'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2022-12-19-grief-and-illness-thornton/