Women’s History Month 2023, 2: Re-reading Alice Thornton's pains and perils

For Women’s History Month 2023, we are posting a series of reflections on our first encounters with Alice Thornton and our changing relationship with her books from then to now. Feel free to get involved by sending us your own reflections on social media.

Second in the series is project postdoctoral researcher Sharon Howard:

CN: childbirth and pain

I first encountered Alice Thornton almost exactly 24 years ago, during the spring term of 1999 when I was studying for an MA in Women's and Gender History at the University of York and took an option on the body in early modern England with Mark Jenner. My interest in women's history had begun several years before that, though, even before I went to university at Aberystwyth and got hooked on early modern history (and a nostalgic wander through undergraduate essays has reminded me that I grabbed every opportunity to write about women and gender that was on offer).

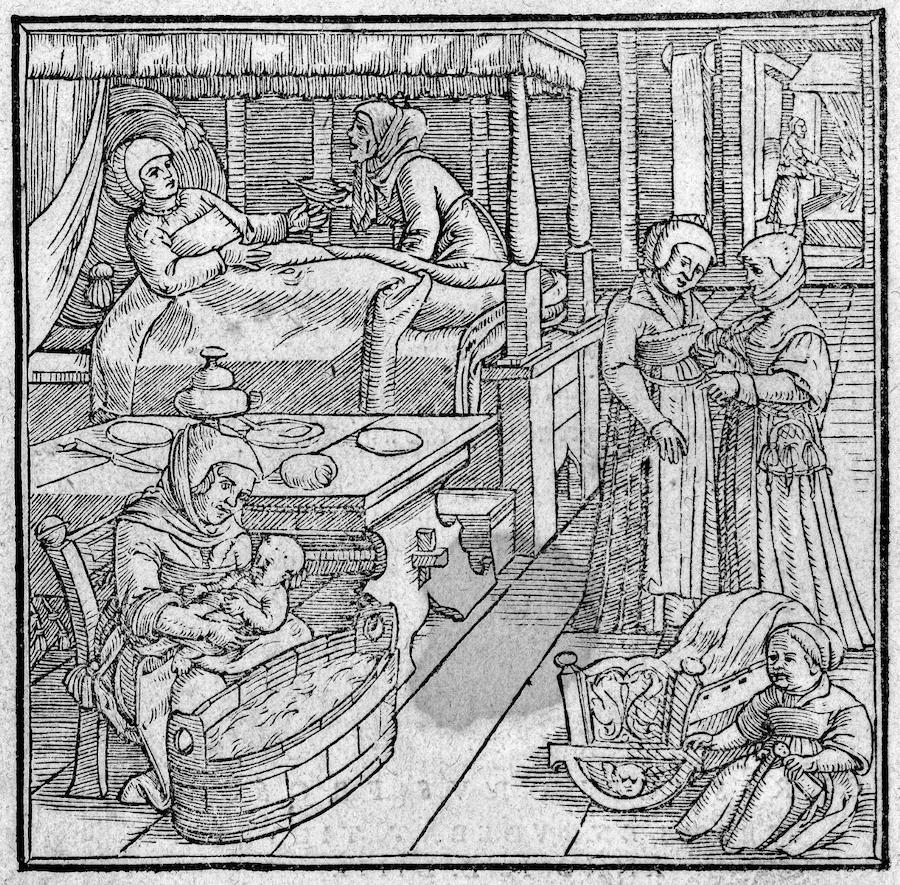

Wellcome Collection, London. CC BY.

I was introduced to Alice through the 1875 Autobiography edited by Charles Jackson, in a seminar on pain and childbirth. It's been noted that many readers have tended - as I did - to focus on Alice's sufferings in illness, pregnancy and childbirth at the expense of other equally significant themes in her books, an emphasis partly influenced by Jackson's editing.[1] But I think it was also influenced by a new wave of research on early modern maternity from the mid 1980s onwards, including key studies of the experiences and meanings of pregnancy and childbirth for mothers.[2] For me in 1999, exploring this emerging field of research was exhilarating and I know I was bowled over by this famous passage in the Autobiography:

the childe staied in the birth, and came crosse with his feete first, and in this condition contineued till Thursday morning betweene two and three a clocke, at which time I was upon the racke in bearing my childe with such exquisitt torment, as if each lime weare divided from other, for the space of two houers; when att length, beeing speechlesse and breathlesse, I was, by the infinitt providence of God, in great mercy delivered.[3]

Reading the Autobiography against this background inspired an essay, which became an article, in which I explored the way she wrote about pain and peril, pregnancy and birth and the providentialism that underpins so much of her writing.[4]

But then I returned to what I had already decided I wanted to research for my PhD: court records, crime and litigation. I spent much of the next 20 years working on thieves and murderers, slanderers, bastard bearers and brawlers. Alice would have mightily disapproved of most of them. Nonetheless, that intervening research has undoubtedly shaped my responses to her writing, and a rather different set of images and themes have caught my attention this time around.

But [Robert Nettleton] prosecuted him with all the rigour could be and false dealing, and treachery against Mr Thornton. And most unjustly & spitefully watched an opportunity when Mr Thornton was at London to have prevented... And one morning very early came with his own man, and four other bailiffs to seize upon all the goods, plate, moneyes [and] whatever else we had in the world till they were all paid their demand and satisfied their debt. And at first the men was very rude and violent [and] I feared they would have seized upon my Person then big with child. But they frighted me very sore... Besides the great and suddenness of the terror and affright this action brought me into, in my condition having but lately escaped death and miscarriage so nearly two times and this fright joined with a hearty grief did bring me very low again, and I expected nothing but a sudden abortion and destruction of my poor infant in my womb.[5]

British Museum, London. CC BY SA.

Alice might have found more in common with the petitioners of my most recent research; the passage echoes many petitioning (and other legal) narratives I've been reading, from the deceitful, unjust malice of her enemies to the threat they posed to both Alice and her unborn child.

Moreover, I now can't help but notice just how often Alice writes of petitioning God (and occasionally people). The prayers and meditations in which this petitionary language are often found were frequently omitted from the Jackson edition, and his omissions also downplayed the importance of the slanderous attack on her reputation in motivating her to write the books.[6] I knew already that her writing was an 'act of self-vindication'.[7] But reading her original manuscripts has newly emphasised for me both the perils created by enemies actively plotting the downfall of Alice and her family and the importance of the friends and relatives who come to her aid. My focus may have shifted, but I continue to be fascinated by Alice's words and her world.

See R. A. Anselment, "Seventeenth-Century Manuscript Sources of Alice Thornton's Life," SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900 45, no. 1 (2005): 135-55 for a comparison of the manuscripts and the Jackson edition. ↩︎

See, in particular, the essays in Valerie Fildes (ed.), Women as Mothers in Pre-Industrial England: Essays in Memory of Dorothy McLaren (London: Routledge, 1990); Adrian Wilson, "The Perils of Early Modern Procreation: Childbirth with or without Fear?," Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 16, no. 1 (1993): 1-19. ↩︎

Alice Thornton, The Autobiography of Mrs. Alice Thornton, of East Newton, Co. York, ed. Charles Jackson, vol. LXII (Durham: Surtees Society, 1875), http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofm00thorrich. ↩︎

Sharon Howard, "Imagining the Pain and Peril of Seventeenth-Century Childbirth: Travail and Deliverance in the Making of an Early Modern World," Social History of Medicine 16, no. 3 (December 1, 2003): 367-82, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/16.3.367. ↩︎

The text quoted here is from our work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes. "But he prosecuted him with all the Rigor could be & fallse dealing, & Treachery against Mr Thornton And most unjustly & spightfully wattched an opportunity when Mr Thornton was att London to have prevented... And one morning very Early came with his owne Man, & 4 other Baylis to seize uppon all the goods Plate Moneyes what ever Ellse we had in the world till they weare all Paid there demand. & sattisfied there Debt. & Att first the men was very Rude and Violent I feared they would have seized uppon my Person then Bigg with Childe. but they frighted me very Sore... Besides the great and sudainess of the Terror & afright this action brought me into, in my Condittion haveing but lately Escaped Death, & miscarriage soe nearely. 2 ty^s^ & this fright Joyned with a hearty greife did bring me very low againe, & I expected nothing but a sudaine Abortion & destruction of my poore Infant in my wombe." Alice Thornton, Book 2: The First Book of My Widowed Condition, Durham Cathedral Library, GB-0033-CCOM 7, 231-33. ↩︎

Anselment, "Seventeenth-Century Manuscript Sources of Alice Thornton's Life." ↩︎

Howard, "Imagining the Pain and Peril of Seventeenth-Century Childbirth," 381. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Sharon Howard. 'Women’s History Month 2023, 2: Re-reading Alice Thornton's pains and perils'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2023-03-08-whm-alice-thornton-pain-peril/