'His Admirable Book': Alice Thornton, Eikon Basilike and Seventeenth-Century Women's Books

Previously, as we approached the anniversary of the execution of Charles I (30 January 1649), Cordelia Beattie explored Thornton’s ‘Curious Account’ of the king’s final days; this year, I will take a closer look at how Thornton records Charles I’s execution. While there are only two explicit references to this event in her four Books, the differences between them raise questions about how they were composed. Furthermore, as her reference to ‘his admirable book’ is clearly an allusion to Eikon Basilike, Thornton’s name can be added to the increasing number of women known to have engaged with ‘The King’s Book’ in the seventeenth century.[1]

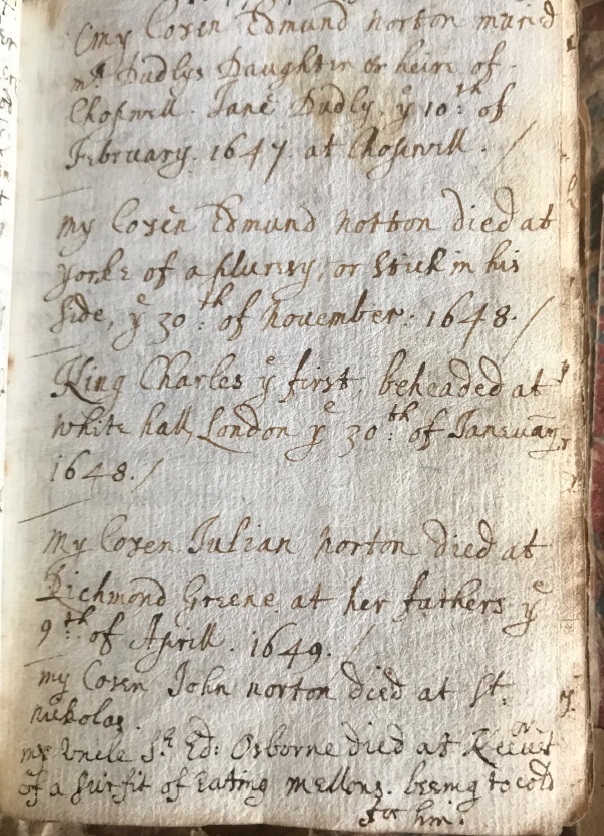

In the Book of Remembrances, Thornton simply recorded it as a single sentence: ‘King Charles I beheaded at Whitehall, London, the 30th of January 1648’.[2] This note is nestled within a list of Thornton’s relatives who are all identified by familial relationship and Christian name, followed by ‘died at’. No cause of death is provided for her cousins Julian and John Norton, although their brother, Edmund Norton, fell victim to pleurisy, and her uncle, Sir Edward Osborne, memorably died of ‘a surfeit of eating melons, being too cold for him’. The combination of the personal and the political here is striking as ‘King Charles I’ is both differentiated from and included within Thornton’s familial network. That framework is also used in Book 1; however, here Thornton provides further details for all those concerned, with the entry on the king being the most extended.[3]

‘Upon the Beheading of King Charles the Martyr, January 30th, 1648’, opens with a clear statement of Thornton’s perception of this event:

Our blessed King Charles I, whose memory shall live to eternity, was cruelly murdered by the hands of blasphemous rebels – his own subjects – at Whitehall, London.[4]

Opening with a collective, possessive pronoun, Thornton assumes her readers share her perspective and proceeds to proclaim, ‘let all true Christians mourn for the fall of this stately cedar’; following the ‘bitter lamentations of Jeremiah’, such ‘true Christians’ should bewail the demise of this ‘holy, pious prince’ who is aligned with Old Testament exemplary rulers: Josiah, Solomon and Hezekiah.

Echoing the phraseology used in both the ‘A Proclamation, for Observation of the Thirtieth Day of January as a Day of Fast and Humiliation’ and ‘A Form of Common Prayer' for ‘the day of the Martyrdom of King Charles the First’, Thornton asks to be delivered ‘from blood guiltiness that it may never be laid to my charge nor my posterity’ and to be spared by God’s mercy.[5]

Thornton squarely places the blame for the king’s murder on ‘the iniquities of his subjects’ whose ‘sins pulled down his ruin on him and ourselves’. It is here that she alludes to the Eikon Basilike:

Let his admirable Book speak his eternal glory and praise, the best of kings (as mere man) that ever this earth had: never defiling himself with sin or blood; of a tender, compassionate, sweet disposition; incomparably chaste and free from the least tincture of vice or profaneness.[6]

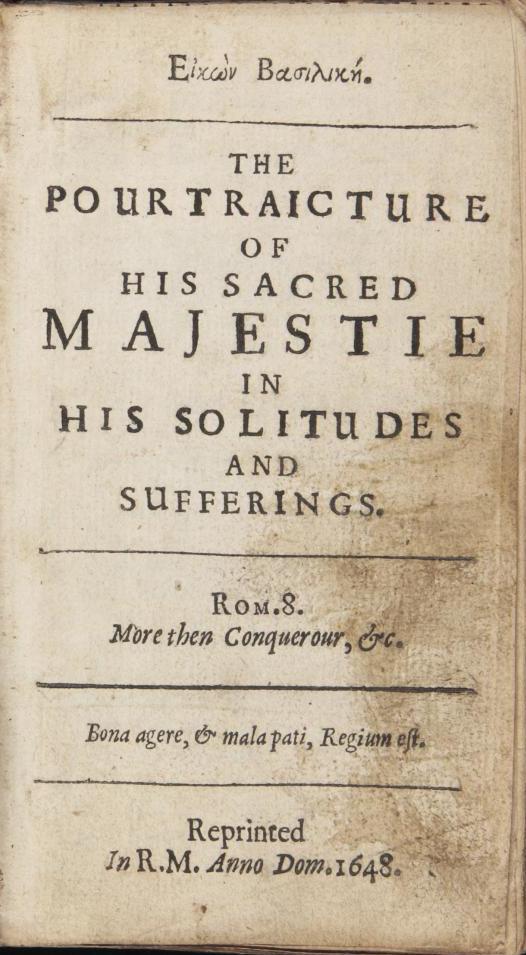

Purporting to represent ‘the Portraiture of His Sacred Majesty in His Solitudes and Sufferings,’ Eikon Basilike made its first appearance on the day of the king’s execution and went through thirty-five editions in England in 1649 alone.[7] Opening with ‘Upon His Majesty’s calling this last Parliament’ and closing with ‘Meditations upon Death,’ Eikon Basilike outlines the major events of Charles I’s life from 1640. Each entry is presented as the king’s first-person account of the titular event and is followed by a prayer in which he pours out his heart to God and begs for his assistance. Thornton’s reflection on the king’s execution is itself a prayer, which, like those in ‘the King’s Book’ is saturated with biblical allusions.

However, while the title of Thornton’s reflection records the historically accurate date of the event, the time at which this entry was written is less certain. Although the Eikon Basilike was published contemporaneously, the ‘Proclamation’ and ‘A Form of Prayer’ appeared in 1660 and 1662 respectively. Furthermore, the likely composition of the Book of Remembrances (c. 1659-73) and Book 1 (c. 1668-87) considerably postdate the event itself.

Like other early modern life-writers, Alice Thornton’s Books reveal various signs of curation that complicate any straightforward sense of immediate testimony. Allusions to other books of meditation in her extant volumes, suggests that she may have copied materials from her other books. Had Thornton already read the Eikon Basilike and written the longer entry that now appears in Book 1 before including the brief record of it in the Book of Remembrances? Or is the later entry supplemented by Thornton’s awareness of ‘the King’s book’ and/or her post restoration experience of the state appointed National Day of Prayer and Fasting?

While there is material evidence that many seventeenth century women owned copies of Eikon Basilike, the organisation of Thornton’s Books, especially Book 1, suggest that she emulates its structure. Like Eikon Basilike, Book 1 is composed of an account of a particular event followed by a prayer, thanksgiving or meditation. Both also include extensive discussion of the trial and execution of the Earl of Strafford, which has personal and political reverberations for the king and Thornton; after all, not only did Thornton socialise with the Earl’s daughters, but it was his return to England that saw her father become Lord Deputy of Ireland.

The fact that women owned, read and imitated ‘the King’s book’ is a powerful reminder of their engagement with the major political events of their time. However, as a forthcoming drama on Radio 4 reminds us, 1649 was not only significant for the king’s execution. It was also the year that the Qu’ran was first published in English – an act that was instigated by the wife of a Fleet Street printer, Margaret White.

For a modernised edition, see Jim Daems and Holly Faith Nelson, eds. Eikon Basilike with Selections from Eikonoklastes by John Milton (Ontario: Broadview, 2006). Rosalind Smith notes that of the 15 copies in the Emmerson Collection, five include marginalia by women; four of those at the Bodleian Library ‘have clear evidence of ownership by women’ as does one in the Turnbull library in New Zealand; Michael Durrant describes similar evidence in two copies deposited at the Senate House Library, and Joseph Black points out that ‘all six copies currently listed in the Private Libraries in Renaissance England project database (plre.folger.edu) are associated with women’ (all accessed 25 January 2025). ↩︎

Alice Thornton, Book of Remembrances (c.1659-73). Modernised edition by Cordelia Beattie, Suzanne Trill, Joanne Edge, Sharon Howard, Paul Caton, Ginestra Ferraro, Geoffroy Noël, Tiffany Ong and Priyal Shah (2024), 25 (accessed 25 January 2025). ↩︎

Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life (c.1668-87). Modernised edition by Cordelia Beattie, Suzanne Trill, Joanne Edge, Sharon Howard, Paul Caton, Ginestra Ferraro, Geoffroy Noël, Tiffany Ong and Priyal Shah (2024), 93-96 (accessed 25 January 2025). ↩︎

‘A Proclamation, for Observation of the Thirtieth Day of January as a Day of Fast and Humiliation’ (London: John Bill, 1660); ‘A Form of Common Prayer, to be used yearly upon the 30. day of January,’ in Brian Cummings, ed., The Book of Common Prayer: The Texts of the 1549, 1559, and 1662 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 655-61; Thornton, Book 1, 94. ↩︎

Robert Wilcher, ‘Eikon Basilike: The Printing, Composition, Strategy, and Impact of “The King’s Book”’, in The Oxford Handbook of Literature and the English Revolution, edited by Laura Lunger Knoppers, 289–308 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Suzanne Trill. ''His Admirable Book': Alice Thornton, Eikon Basilike and Seventeenth-Century Women's Books'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2025-01-29-Eikon-Basilike-Blog/