Women's History Month 2024, 2: Alice Thornton and Our Imagined Alice Thorntons

March is Women's History Month and, like last year, to mark it we’re bringing you a series of blog posts. In this second post, our Engagement and Impact Officer Eleanor Thom writes about the missing portraits of Alice Thornton and how we imagine her.

What did Alice Thornton look like?

Since work began on a digital edition of the once missing books of Alice Thornton (1626-1707), one of the most common questions our team of researchers has been asked is: What did Alice Thornton look like? The answer is, we would love to know, and maybe one day we will. Out there somewhere there is at least one missing portrait of Alice Thornton. In her will, she left ‘my dear husband’s picture and my own’[1] to her grandchildren. Were these separate portraits or a joint one of the couple?

We know that a painting of Alice Thornton was in the possession of the Comber family in 1875. It was described, according to Jackson , as 'not a striking one. It represents a middle-aged lady, clad in widow's weeds, which she probably wore to the end of her days'.[2]

Unfortunately, since the 1875 reference to that portrait was made, its whereabouts have been a mystery. Equally, there has been no mention of a portrait in which Alice was depicted alongside her husband, William Thornton.

Portraits of Thornton's father

While we hope the paintings may one day be recovered, in the meantime, we have sometimes shared an image of the closest relative of Alice who we do have an portrait of: her father, Christopher Wandesford (1592-1640). Previously, we had only seen the 19th-century copy of this 17th-century portrait, but we are now in touch with the line of descendants who own the original. We have their kind permission to share it here. As well as this painting, the Prior-Wandesforde family own a second original portrait of Christopher Wandesford.

Suggestions that Alice Thornton may have had red hair have arisen because her father’s portraits hint at a redheaded gene. This is Charles Jackson's description of the portrait: ‘a fair, oval-faced man, with a sanguine complexion and auburn hair’.[3] Could Alice have had red hair? One branch of Thornton's descendants say they have no relatives with red hair today, and another say they do have a ginger gene. Genes that determine physical characteristics can travel through the centuries down one branch of a family tree and disappear from others entirely, and sadly, we have nothing to prove Alice Thornton inherited her father’s hair colour either way.

Vanishing Historical Women

Just before joining Alice Thornton's Books as the team’s Engagement and Impact Officer, I read A Ghost in the Throat by Irish author Doireann Ní Ghríofa.[4] It is a brilliant book, part essay, part auto-fiction about the daily life of a mother with young childen. It is also a new translation of an 18th-century Gaelic poem written by a female member of the Irish gentry, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill (c.1743–1800), not quite a contemporary of Alice Thornton, but not too far off. In A Ghost in the Throat, Ní Ghríofa goes to desperate lengths to do the virtually impossible: reach into the shadows of history to try and unveil the woman who wrote this poem. Ní Ghríofa is defiant in her quest despite the distinct lack of information that exists on Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill: essentially, there is none. Where Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill is recorded at all, it’s as brief aside in paragraphs about the men she was related to. Her erasure is felt not just by the narrator, but by the reader too, a palpable agony of not knowing.

For Doireann Ní Ghríofa, as for the Alice Thornton’s Books team, there was no image of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, only that of her more famous male relative, nephew, Dónall Ó Conaill (1775–1847).

Thornton in the Archives

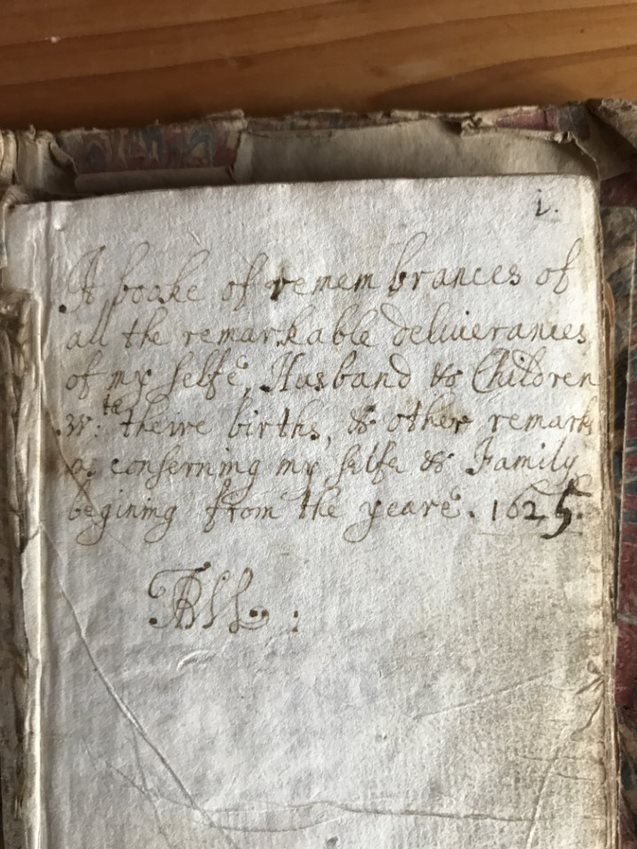

The Thornton Books team is, by comparison, lucky beyond belief. We have held the books Thornton held. One of them (The Book of Remembrances) is perhaps even bound together by Thornton's own hand. Inside these books, we can read the story of Thornton's life in her own words. As well as this, in archives around the UK and Ireland we have found letters and legal documents, and out in the world there are buildings still standing that Alice Thornton inhabited.

Even without seeing a portrait of Thornton, which could be anywhere, in an archive, in a private collection, in a junk shop, a gallery, or in someone’s attic, we can draw some conclusions from the fact that paintings of her existed at all. In the seventeenth century, money and influence decided whose face would be recorded along with their name and their story. Men were often the subjects, but there is nevertheless a significant body of early modern artwork visually representing widowhood.

It’s not known who commissioned the painting of Alice Thornton in widow’s weeds. It would be easy to assume she commissioned the work herself, but most portraits of widows from this time, where commissions and contracts can be traced, were paid for by male patrons. In her essay, 'Framing Widows', Allison Levy reveals that occasionally wives in England were painted as widows even before the deaths of their husbands, and that in some cases their husbands actually outlived them.

Levy explains:

If male portraiture memorializes the sitter, representing ‘the dead to the living many centuries later,’ as Alberti suggests, then widow portraiture not only memorializes the husband, but it also provides him with a perpetual mourner. In other words, not only is the husband remembered, but he is also remembered in what was considered to be an ideal manner – by a virtuous and chaste widow.[5]

So perhaps Alice Thornton wished to be remembered as a virtuous woman in widow’s weeds, but we can’t say for certain that the style of her portrait was directed entirely by her, or that the intention behind it wasn’t her husband’s eternal remembrance rather than her own. We know that Thornton was writing and rewriting her books in the years following her husband’s death, when she feared her reputation was damaged by rumours spread by her niece and others. She tells us, in her own words, that her books are part of her defence. Was this portrait part of that defence too?

Imagining Alice

Alice Thornton’s facelessness, on the face of it, is a pity. It’s impossible to completely disable the imagination when you read her words. She is expressive and honest on the page, and this is a quality that lends itself to feeling you have come to know her, as you would a fictional character. But she is not fictional, and a representation of her would helpfully signal that. She was a real person with a real family. Moreover, the figurehead of the Thornton Books project shouldn’t forever be the portrait of her father, so although we include it on the homepage of our website, elsewhere we use Alice Thornton’s monogram which she added to three of her books.[6]

Thornton’s image remaining a mystery means that each member of the Thornton’s Books team has their own imagined version of her and, whenever we meet, she is somehow a presence. This has been helpful at times, because our imagined Alice Thorntons sometimes suggest alternative readings of her text. For example, working closely with the Thornton’s Books team, writer and performer, Debbie Cannon’s theatrical Alice Thornton – who you could encounter live on stage in several upcoming performances in 2024 - is the version which really captured and underlined the humour in Thornton’s original words.

Project Principal Investigator, Cordelia Beattie admits that finding a portrait of Alice Thornton, eventually, would be ‘the icing on the cake’, and we remain hopeful that one day one may turn up.

In 2018, a portrait of Charles Dickens painted by Margaret Gilles, which had been missing for over 150 years, suddenly reappeared in South Africa. It was being sold for about £27 inside a ‘box of junk’ and was covered in fungus and mould. Restored, it is now displayed in London.

With luck, an Alice Thornton portrait might turn up too, and perhaps a little closer to home, but wherever you are reading this, please keep your eyes peeled just in case. Her likeness is out there, somewhere.

Charles Jackson. Ed. The Autobiography of Mrs. Alice Thornton of East Newton, Co. York. Durham: Surtees Society, 1875, 335. ↩︎

Jackson, Autobiography, xiv. ↩︎

Jackson, Autobiography, vi. ↩︎

Doireann Ní Ghríofa, A Ghost in the Throat (Dublin: Tramp Press, 2000). ↩︎

Allison Levy, 'Framing Widows, Mourning, Gender and Portraiture' in Widowhood and Visual Culture in Early Modern Europe, ed. Allison Levy (Aldershot: Routledge, 2003), 223. ↩︎

Alice Thornton, Book of Remembrances, Durham Cathedral Library (DCL), GB-0033-CCOM 38, 1; Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life, British Library MS Add 88897/1, 301; Alice Thornton, Book 3: The Second Book of My Widowed Condition, British Library MS Add 88897/2, 1. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Eleanor Thom. 'Women's History Month 2024, 2: Alice Thornton and Our Imagined Alice Thorntons'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2024-03-08-imagined-alices/