Women's History Month 2024, 4: Alice Thornton and the North American Connection

March is Women's History Month and to mark it - like last year - we’re bringing you a series of blog posts, this time on Alice Thornton and various women that feature in her writings. In this instalment, Professor Patricia Phillippy - who is writing an essay on climate and colonisation for our Thornton book - explores Thornton’s relationships with North American sojourners, Martha Batt and Anne Danby, and with Danby’s maid, Barbara Todd.

American Sojourners

In 1652, in Virginia, one Anne Culpeper married Thornton’s nephew, Christopher Danby. Anne’s later account describes the events leading up to this union:

Sir Thomas Danby in the late troublesome times, sent over into Virginia (under the conduct of one Captain Batt) his second and third sons Mr Christopher and Mr John Danby, with purpose to come over and settle there himself; in order to which he differed, and entrusted with this prementioned Captain Batt, some considerable sum of money laid out in servants and goods out of which he bought a plantation; which cost £150 in goods the first penny in England. About which time my dear and worthy father Mr John Culpeper having been a deep sufferer for his loyalty to his late Majesty (Charles the first) was forced to fly with his family into Virginia, where he died, after whose death it was my unhappy fate (as it has since proved) to marry this second son of Sir Thomas Danby (Mr Christopher).[1]

Anne Danby’s unhappy fate began immediately after marriage. Her first child, born in 1653, lived only days. Moreover, although Sir Thomas Danby, Thornton’s brother-in-law, had acquired the Virginia plantation of Buckrow for his son, he did not provide adequate ‘household stuff and servants’ for the couple.[2] By 1655, Sir Thomas Danby had recalled his son to England, with Anne accompanying him.

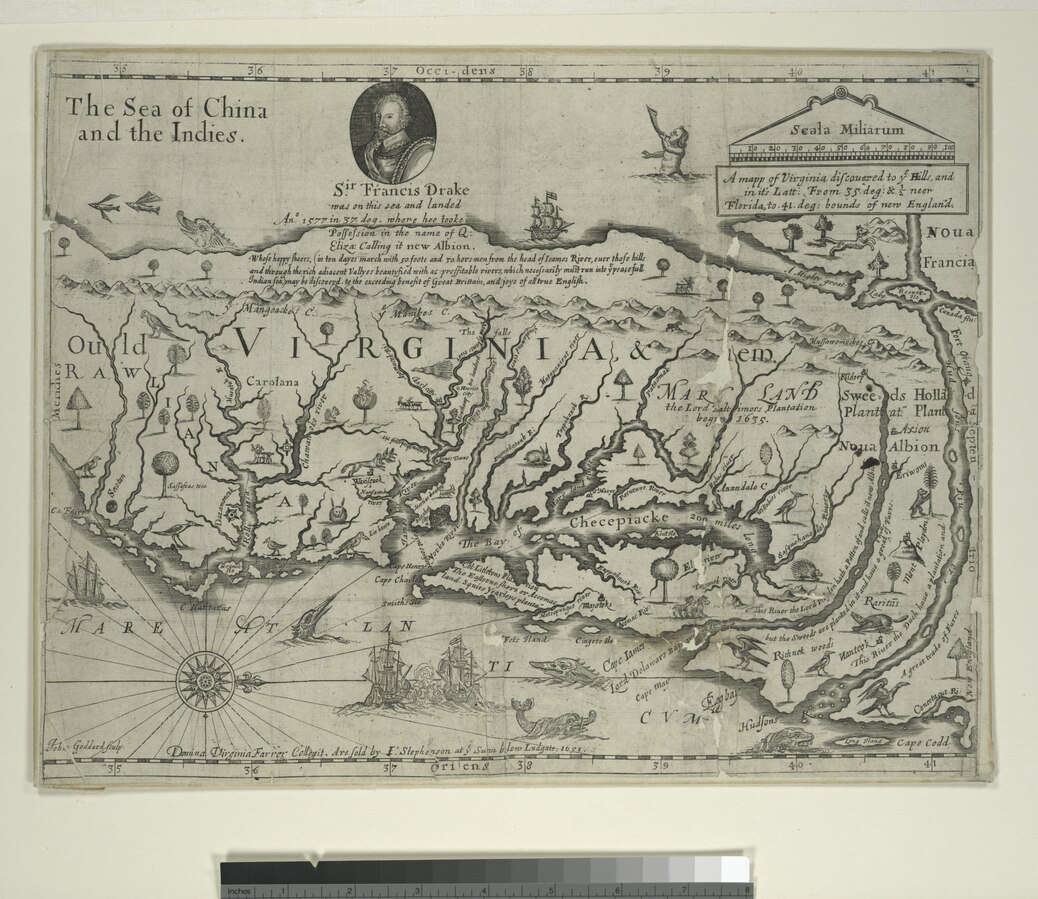

Sir Thomas Danby’s interest in settling in North America was piqued by a lease of 10,000 acres granted to him by Sir Edmund Plowden, ‘Lord Earl Palatinate, Governor and Captain-General of the Province of New Albion in North America’.[3] Plowden’s venture to settle New Albion in land ‘inhabited by a barbarous and wild people’,[4] was ill-fated. His initial voyage in 1642, ‘for want of a pilot’, landed in the Virginia colony rather than north of the Delaware River as planned.[5] He never established his colony and returned to Ireland in 1649, to promote this notional territory from afar.

The afterlife of New Albion and the English colonial project subtly permeated Thornton’s life. Among those named in Plowden’s will in 1659 were members of the North Yorkshire coterie surrounding Thornton. The will provided that Danby and ‘Captain Batt his heir’ each should ‘transplant’ 100 settlers to New Albion annually. In 1650, Sir Thomas Danby and Captain John Batt were granted a pass ‘for themselves and seven score men, women, and children to go to New Albion’.[6] Batt’s wife and unmarried daughter, Martha (who accompanied Batt to New Albion) were in Thornton’s circle.

The transmigrations of the Batt and Danby families identify transatlantic ‘sojourners’ as opposed to settlers. They place Thornton in a circle of women whose Atlantic sojourns, knowledge, attitudes and experiences involved Thornton herself in global networks of exchange, placing her in a far greater world than the confines of women’s domestic experience and life writings are generally afforded.

Anne Danby and Martha Batt

These attitudes are on display in an episode recounted in Thornton’s books involving Anne Danby and Martha Batt: the dispute centred on a rivalry to arrange a match in marriage to Thomas Comber before Comber’s marriage to Thornton’s daughter, Nally, in 1668. Danby ‘prosecuted with eager design for to draw him in for a husband for Mrs Batt’,[7] i.e., Martha. Rumours began to circulate concerning an extramarital affair between Thornton and Comber.

During this period, Martha Batt tells Thornton:

That she had seen a letter in Virginia that came to Mrs Danby from Sir Thomas out of England … that was extremely sharp, where he told her that she had inveigled his son to marry her without his consent and their marriage was not lawful … and was so incensed that he would never see her in all his life but shunned her at all times, sending for his son into England without her.[8]

The passage reveals the persistence of transatlantic alliances and disputes, among a group of female sojourners, and varying degrees of dependency and autonomy both in America and England. The claim attributed to Thomas Danby that Anne ‘inveigled’ his son, memorialised by Martha Batt, is repeated by Thornton to affirm Anne Danby’s ‘so secret and subtle’ abuses against her.

As the dispute escalated, Thornton suffered from slanders put forth by Danby and her household. Her account includes this fascinating detail:

Even so was I and my poor child accused and condemned before her, in her chamber, by her said servant in a most notorious manner. And all my chaste life and conversation most wickedly traduced, so that she railed on me and scolded at me and my poor innocent child, before our faces, with the most vile expressions... Such was the fury of Barbary’s malice against us that, with a brazen face she impudently cried out against me.[9]

A Maid Called Barbary

Anne Danby’s maid was Barbara Todd.[10] Thornton’s reference to her as 'Barbary' resonates with the period’s usages of this name, particularly as ascribed to servants and social inferiors. Danby, too, refers to her as ‘Barbary’,[11] and Thornton’s sister Katherine Danby had a servant called Barbary Wren.[12]

If this rendering of Barbara as Barbary typically referred to women in service, increasingly its racial associations concocted a name that blended class and race. Both Barbara and Barbary are derived from 'barbarus', meaning ‘foreigner’ or ‘stranger’. As the Black population of early modern England increased — comprised of enslaved Africans and Indigenous people of the Americas — the name Barbary was commonly assigned to or adopted by women of colour.

The ‘treacherous and lascivious blackamoor maid’ became a stereotype on the seventeenth-century stage.[13] Desdemona’s recollection of her mother’s maid Barbary complicates the racial economy of Othello, suggesting an affinity between herself and this Black servant. When not in service, these women were often litigants, particularly in prostitution cases, which display ‘the marking of blackness as a prohibited social pathology in its deployment in the sexual commodification of black women’.[14] Barbary, as Thornton portrays her, shared her mistress’s problematised sexuality, ‘brazen face’ and impudence.

The availability of 'Barbary' as a derogatory label reveals how the colonial project complicates even as it creates entangled differences of gender, class and race. It put into Thornton’s hands the terms with which to demonize the maid Barbary as a racialized other. These women, like the Black servants in New Albion, are essentially ‘alien’.

The quotidian concerns of Thornton’s Books, much like those of other manuscript writings by early modern Englishwomen, may seem parochial, even trivial. But, by casting a global worldview on Thornton’s writings, we can begin to trace the worldwide effects of colonialism across the British Atlantic and the ripples they sent through everyday life.

Anne Danby, ‘An accompt of all the transactions of any note that remains with in the Compasse of my memory since my marriage with Mr Christopher Danby’, 1683, ZS – Swinton and Middleham Estate Records (MIC 2281), North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO), Northallerton. I am grateful to the Alice Thornton's Books project for sharing their transcriptions with me. ↩︎

'Philip Mallory to Thomas Danby, July 10th 1653', Danby family letters & papers c. 1620–1687, ZS (MIC 2087/1762), NYCRO; and 'Mallory to Danby, February 14, (1653/4)'. ↩︎

‘The Will of Sir Edmund Plowden, July 27, 1659', PROB 11/294/364, The National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

‘A true copy of the Grant of King Charles I to Sir Edmund Plowden Lord Palatine of Albion in America’, in Walter F. C. Chicheley Plowden, Records of the Chicheley Plowdens (London: Heath, Cranton & Ouseley, Ltd., 1914), 81. Plowden’s first petition is TNA CO 1/6, ‘The humble petition’. ↩︎

See John Winthrop, Winthrop’s Journal: ‘History of America,’ 1630-1649, ed. James Kendall Hosmer, 2 vols (New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1908), vol. 2, 343. ↩︎

‘The Will of Sir Edmund Plowden’; Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies, Volume 1, 1574-1660 edited by W. Noel Sainsbury (London: HMSO, 1860), 340. ↩︎

The text quoted above is from the project's work-in-progress edition of Alice Thornton's Books. The text is modernised in the body of the blog and the semi-diplomatic transcription is reproduced here in the notes. ‘Prosecuted with eager designe for to drawe him in for a husband for Mrs Batte’. Alice Thornton, Book 1: The First Book of My Life, BL MS Add 88897/1 (hereafter Book 1), 238. ↩︎

‘That she had seene a letter in Virginia that came to Mrs Danby from Sir Tho. out of England…that was extreamly sharpe. where he tould her that she had inveagled his son to marry her with out his consent & theire marriage was not Lawfull… & was soe incensed that he would never see her in all his Life but shunned her at all times, sending for his son into England with out her’. Thornton, Book 1, 236. ↩︎

‘Even so was I and my poore child accused and condemned before her in her chamber by [Mistress Danby’s] servant in a most notorious manner, and all my chaste life and conversation most wickedly traduced, soe that she railed on me and scoulded at me and my poore innocent child, before our faces, with the most vile expressions could be imagined... Such was the fury of Barbary's mallice against us that with a brasen face she impudently cryed out against me, and said that ‘I was naught, and my parents was naught, and all that I came on was naught’. Alice Thornton, Book 3: The Second Book of My Widowed Condition, BL MS Add 88897/2, 192. ↩︎

Alice Thornton, Book 2: The First Book of My Widowed Condition, DCL MS GB-0033-CCOM 7, 16. ↩︎

'Anne Danby to Parson Farrer, 10 December (1668/69)', Cunliffe Lister Muniments [MIC 2281], NYCRO, unnumbered page 2. ↩︎

See 'Barbary Wren to Katherine Danby, 9th November 1637', ZS (MIC 2087/1512), NYCRO. ↩︎

Iman Sheeha, ‘"(A) Maid Called Barbary": Othello, Moorish Maidservants and the Black Presence in Early Modern England’, Shakespeare Survey 75 (2022): 99, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009245845.007. ↩︎

Imtiaz Habib, Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible (London: Routledge, 2008), 107–108. ↩︎

Citing this web page:

Patricia Phillippy. 'Women's History Month 2024, 4: Alice Thornton and the North American Connection'. Alice Thornton's Books. Accessed .https://thornton.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/posts/blog/2024-03-21-thornton-and-north-america/